#17,357

While H5N1's endgame is far from assured, it continues to make news as it spills over into mammals around the globe. Over the past 7 days alone, we've seen:

UK Reports 2 Dolphins With HPAI H5N1 & EID Report On Infected Harbor Porpoise in Sweden

CDC EID Journal: HPAI A(H5N1) Virus Outbreak in New England Seals, United States

PLoS Pathogens: Evolution of Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza A Virus in the Central Nervous System of Ferrets

British Columbia Press Release: Government Reports 8 Skunks Infected With HPAI H5N1

Preprint: Pathology Of HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b in Wild Terrestrial Mammals in the United States in 2022

Emerging Microbes & Inf.: Neurotropic HPAI H5N1 Viruses with Mammalian Adaptive Mutations in Free-living Mesocarnivores in Canada

Earlier this week, in ECDC/EFSA Avian Influenza Overview December 2022 – March 2023, researchers described recent changes to the virus that may make it more of a threat to mammalian hosts.

Mutations identified in A(H5N1) viruses from mammals

About half of the characterized viruses contain at least one of the adaptive markers associated with an increased virulence and replication in mammals in the PB2 protein (E627K, D701N or T271A) (Suttie et al., 2019). These mutations have never (T271A) or rarely (E627K, D701N) been identified in the HPAI A(H5) viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b collected in birds in Europe since October 2020 (<0.5% of viral sequences from birds).

This observation suggests that these mutations with potential public health implications have likely emerged upon transmission to mammals. Moreover, the viruses collected in October 2022 from a HPAI A(H5N1) outbreak in intensively farmed minks in northwest Spain (Aguero et al., 2023) shows mutations in the NA protein which cause disruption of the second sialic acid binding site (2SBS). This feature is typical of human-adapted influenza A viruses, which may favour the emergence of mutations in the receptor binding site of the HA protein (de Vries and de Haan, 2023). These same mutations were detected also in seven A(H5N1) viruses from birds.

All of which means, that while often repetitive, reports of additional spillovers into mammals are of great importance.

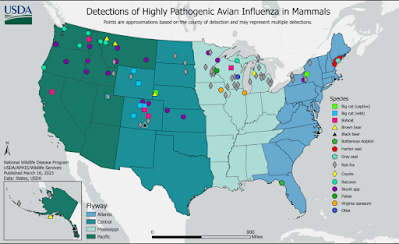

Yesterday the USDA updated their list of confirmed mammalian infections from H5N1, adding 4 new cases since their last update on March 9th. This brings the number of laboratory confirmed H5N1 positive mammals in the United States to 148, although that likely represents only a tiny faction of the actual number of mammals infected.

Added were 3 skunks and a raccoon (see list below).Research and analysis

Confirmed findings of influenza of avian origin in captive mammals

Published 17 March 2023

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

Details of confirmed findings of influenza of avian origin in captive mammals in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales).South American bush dogs, March 2023

Ten South American bush dogs (Speothos venaticus venaticus) have tested positive for highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) in March 2023.

These animals were part of a captive breeding programme at a zoological premises in England. They were tested as part of a routine investigation into an unusual mammal die-off in November 2022. Ten animals died or were euthanised in a group of 15 bush dogs, over a 9 day period.

The bush dogs had minimal clinical signs before death, and APHA cannot definitively state whether or not H5N1 caused the clinical signs. Influenza of avian origin was not suspected at the time; the virus has since been detected in postmortem samples.

There is no clear evidence suggesting mammal to mammal transmission. It is very likely all animals were exposed to the same source of infected wild birds.

It's not clear why it took nearly 5 months to identify the cause of this unusual mortality event, although the lack of overt symptoms may have been a factor. We've seen ample evidence in the past that dogs and other canids are susceptible to HPAI H5 viruses, including:

J. Vet. Sci.: Experimental Canine Infection With Avian H5N8

Norwegian Veterinary Institute Reports Avian H5N1 Spillover Into Red Foxes

MAFRA: H5N8 Antibodies Detected In South Korean Dogs (Again)

Given the susceptibility of both dogs and cats to avian influenza (see HPAI H5: Catch As Cats Can), and the elevated levels of the virus in wild birds, it makes sense to heed the advice of the CDC and other health entities when it comes to protecting your companion animals from infection.

As a general precaution, people should avoid direct contact with wild birds and observe wild birds only from a distance, whenever possible. People should also avoid contact between their pets (e.g., pet birds, dogs and cats) with wild birds. Don’t touch sick or dead birds, their feces or litter, or any surface or water source (e.g., ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with their saliva, feces, or any other bodily fluids without wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).

More information about specific precautions to take for preventing the spread of bird flu viruses between animals and people is available at Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People. Additional information about the appropriate PPE to wear is available at Backyard Flock Owners: Take Steps to Protect Yourself from Avian Influenza.