#17,482

The avian flu situation has changed markedly in the 7 months since we first looked at a Preprint: Rapid Evolution of A(H5N1) Influenza Viruses After Intercontinental Spread to North America, which described the detection of multiple new genotypes of H5N1 - some with increased virulence - which evolved after the H5N1 virus crossed the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in Canada in late 2021.

At the time, the authors wrote:

From a public health perspective, the increased pathogenicity of the reassortant A(H5N1) viruses is of significant concern. However, this is tempered by the avian virus–like characteristics of the viruses with respect to their receptor binding preference and their pH of HA activation. These characteristics probably need to change to enable sustained human-to-human transmission, although only a few amino acid changes among various influenza proteins are needed to switch these properties during adaptation in mammals.

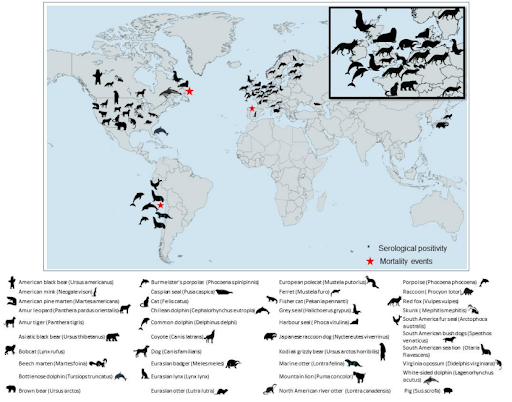

Within weeks of its publication we saw the H5 virus spread southward for the first time along the South American Pacific coast, followed by reports of hundreds (then thousands) of marine mammal deaths from Peru to Chile.

As we've seen in North America and Europe, new genotypes have emerged in South America as well (see Preprint: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in Marine Mammals and Seabirds in Peru).

Also in the fall of 2022, Spain reported an Avian H5N1 Spillover Into Farmed Mink, which we would later learn (see Eurosurveillance: HPAI A(H5N1) Virus Infection in Farmed Minks, Spain, October 2022) not only suggested possible mammal-to-mammal transmission of the virus, but it also produced a rare `mammalian' mutation (T271A), which `enhances the polymerase activity of influenza A viruses in mammalian host cells and mice'.

UK Reports 2 Dolphins With HPAI H5N1 & EID Report On Infected Harbor Porpoise in Sweden

PLoS Pathogens: Evolution of Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza A Virus in the Central Nervous System of Ferrets

Human infections with this new H5 virus have been rare, but have increased and have ranged from mild or asymptomatic to life threatening. Since testing and surveillance is sporadic at best (see UK Novel Flu Surveillance: Quantifying TTD), it is likely some cases have been missed.

This week Nature published the final version of the preprint mentioned at the top of this blog (see below), which has generated a good deal of buzz in the media this week (see Experts warn bird flu virus changing rapidly in largest ever outbreak).

Ahmed Kandeil, Christopher Patton, Jeremy C. Jones, ,Trushar Jeevan, Walter N. Harrington, Sanja Trifkovic, Jon P. Seiler, Thomas Fabrizio, Karlie Woodard, Jasmine C. Turner, Jeri-Carol Crumpton, Lance Miller, Adam Rubrum, Jennifer DeBeauchamp, Charles J. Russell, Elena A. Govorkova, Peter Vogel, Mia Kim-Torchetti, Yohannes Berhane, David Stallknecht, Rebecca Poulson, Lisa Kercher & Richard J. Webby

Nature Communications volume 14, Article number: 3082 (2023) Cite this article

Abstract

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b underwent an explosive geographic expansion in 2021 among wild birds and domestic poultry across Asia, Europe, and Africa. By the end of 2021, 2.3.4.4b viruses were detected in North America, signifying further intercontinental spread. Here we show that the western movement of clade 2.3.4.4b was quickly followed by reassortment with viruses circulating in wild birds in North America, resulting in the acquisition of different combinations of ribonucleoprotein genes.

These reassortant A(H5N1) viruses are genotypically and phenotypically diverse, with many causing severe disease with dramatic neurologic involvement in mammals. The proclivity of the current A(H5N1) 2.3.4.4b virus lineage to reassort and target the central nervous system warrants concerted planning to combat the spread and evolution of the virus within the continent and to mitigate the impact of a potential influenza pandemic that could originate from similar A(H5N1) reassortants.

While H5N1 has threatened unsuccessfully before, one can't help but feel that this time things are different. The virus is far more widespread than ever, not only in terms of geography, but also in the number of species (avian and mammalian) it is affecting.

H5N1 is also a blanket term for scores of similar - but genetically distinct - genotypes, all of which continue to evolve and diversify. We aren't just facing one wayward H5N1 virus with pandemic potential, we are potentially facing dozens.

Although we'd seen some hints of neurological impacts from H5N1 in the past (see 2015's CJ ID & MM: Case Study Of A Neurotropic H5N1 Infection - Canada), it was considered a rare presentation. The authors of that report did warn, however:

These reports suggest the H5N1 virus is becoming more neurologically virulent and adapting to mammals.

In a 2015 Scientific Reports study on the genetics of the H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1c virus - Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Struck Migratory Birds in China in 2015 – the authors warned of its neurotropic effects, and that it could pose a ` . . . significant threat to humans if these viruses develop the ability to bind human-type receptors more effectively.'

Although the name is the same, the H5N1 virus of today is a far cry from the virus that emerged in Southeast Asia two decades ago.

HPAI H5 was initially limited to Southern China and parts of Southeast Asia, where it smoldered in poultry and wild birds until it evolved into clade 2.2 at Qinghai Lake - and then quickly spread to Europe, the Middle East, and Africa - in 2005-2007.

A new H5N8 clade 2.3.4.4 emerged in South Korea in 2014, breathing new life into the H5 subtype, spreading with unexpected vigor around the globe, and reassorting readily with other LPAI viruses. In 2016, a reassortment event in Russia or China further increased its ability to be carried by migratory birds.For the next decade it set up housekeeping in places like Egypt, Cambodia, and Indonesia - forming geographically distinct clades and variants - but by 2012 H5 appeared to be declining globally.

Since then HPAI H5Nx viruses have undergone numerous and rapid evolutionary changes, morphing from H5N8, to H5N6, and more recently to H5N1 and H5N5 subtypes.

Not surprisingly, H5's evolutionary rate has increased as the number and variety of H5 viruses in circulation has grown. Exactly where this uncontrolled global field experiment will lead remains to be seen, but additional changes to the virus are inevitable.

We need to be prepared for surprises ahead. And time is not our friend.