Zoonotic Disease Pathways

#17,864

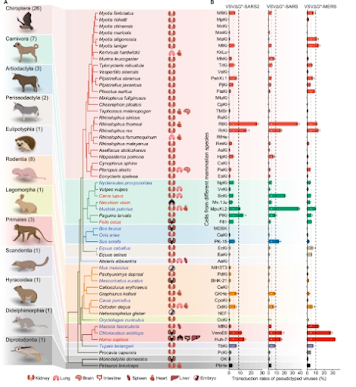

While governments and health agencies have declared the COVID emergency to be over - and the public clearly longs to put our protracted pandemic behind us - SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve, adapt, and expand its host range.Numerous variants of SARS-CoV-2 now circulate - alongside MERS-CoV, and dozens of other coronaviruses - in scores of mammalian species, all following divergent evolutionary paths (see Nature: Comparative Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV Across Mammals).

The SARS-CoV-2 virus was undiscovered until it emerged in late 2019, but scientists had been warning of some thing `like it' for years (see 2016's PNAS: SARS-like WIV1-CoV Poised For Human Emergence).

In October of 2019, a novel coronavirus (CAPS - Coronavirus Acute Pulmonary Syndrome ) was selected as the fictional pandemic pathogen in a major tabletop exercise (see JHCHS Pandemic Table Top Exercise (EVENT 201) Videos Now Available Online).

While SARS-CoV-2 is exquisitely adapted to human hosts, it has also branched out to other mammals, and we've seen evidence that the virus can mutate and evolve in those non-human hosts and then spill back into humans.

In late 2020 we saw SARS-CoV-2 jump from humans to farmed mink in Denmark, spread like wildfire, mutating into new mink-variants (see Denmark Orders Culling Of All Mink Following Discovery Of Mutated Coronavirus), several of which spilled back into the community.

That emergency was short-lived since the Alpha variant emerged in Europe in late 2020 and quickly supplanted those mink variants. But since then, we've seen repeated spillovers into mink (see Eurosurveillance: Cryptic SARS-CoV-2 Lineage Identified on Two Mink Farms In Poland).

In late 2021 a new, and highly divergent Omicron virus emerged in South Africa, and while unproven, there is plausible scientific evidence to suggest it may have first evolved in rodents (see Maryn McKenna's Wired article Where Did Omicron Come From? Maybe Its First Host Was Mice).

This theory is backed up by several studies, including:

Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant

Structural basis for mouse receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant

Structural Evidence that Rodents Facilitated the Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant

We've also seen evidence that older COVID variants - including those no longer circulating in humans - can be maintained in other host populations (see PNAS: White-Tailed Deer as a Wildlife Reservoir for Nearly Extinct SARS-CoV-2 Variants), and may then follow new, and divergent evolutionary paths.

We've seen other cautionary reports - including CCDC Weekly Perspectives: COVID-19 Expands Its Territories from Humans to Animals from China - which warn that the spillover of COVID into other species provides the virus with new opportunities to evolve, adapt, and potentially return with a vengeance.

How often SARS-CoV-2 infects animals in the wild remains largely unknown, but the spillover of the virus into other species is increasingly viewed as a serious threat (see WHO/FAO/OIE Joint Statement On Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 In Wildlife & Preventing Formation of Reservoirs).

All of which brings us to a new EID Journal Dispatch, published this week, on the experimental infection of Elk and Mule Deer with SARS-CoV-2, which - unlike White-Tailed Deer (WTD) - have not previously been identified as susceptible species.

While Elk were not particularly susceptible to the virus, Mule deer proved to be a far better host.

Volume 30, Number 2—February 2024Dispatch

Author affiliations: US Department of Agriculture, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA (S.M. Porter, J.J. Root); Colorado State University, Fort Collins (A.E. Hartwig, J.M. Marano, A.M. Bosco-Lauth); University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia (H. Bielefeldt-Ohmann)

Abstract

To assess the susceptibility of elk (Cervus canadensis) and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) to SARS-CoV-2, we performed experimental infections in both species. Elk did not shed infectious virus but mounted low-level serologic responses. Mule deer shed and transmitted virus and mounted pronounced serologic responses and thus could play a role in SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology.

(SNIP)

Conclusions

If wildlife populations serve as maintenance hosts for SARS-CoV-2, the implications could be substantial. The persistence of virus variants already displaced in the human population, virus evolution, and spillback into a human have all been suggested to have occurred in white-tailed deer populations (11,12), although it is still unclear whether those deer will serve as maintenance hosts of the virus. Evaluating the susceptibility of other cervid species to SARS-CoV-2 will help direct surveillance efforts among free-ranging wildlife, which are key to understanding the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 and implementing control measures.

We used the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 to challenge animals in this experiment on the basis of evidence that this variant of concern was prevalent in white-tailed deer populations (13). Our results indicate that although elk seem to be minimally susceptible to infection with the Delta variant, mule deer are highly susceptible and capable of transmitting the virus. Inoculated elk showed no clinical signs, did not shed infectious virus, and mounted low-level humoral titers. The genomic RNA recovered from elk could represent residual inoculum. Infection in mule deer was subclinical, and although immune activation in the absence of frank inflammation was observed in respiratory tissues from 4 of the 6 animals, that finding may or may not be linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of note, all mule deer used in this study were incidentally tested to assess their chronic wasting disease (CWD) status. Animals no. 1 and 3 were CWD positive, although it is unlikely that a concurrent infection with CWD greatly affected their susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because only 1 of those animals became infected with SARS-CoV-2 while the other was the sole mule deer in our study that did not.

Experimental infection of elk and mule deer with SARS-CoV-2 revealed that although elk are minimally susceptible to infection, mule deer become infected, shed infectious virus, and can infect naive contacts. Mule deer are less widely distributed than white-tailed deer but still represent a population of cervids that is frequently in contact with humans and domestic animals. Therefore, susceptibility of mule deer provides yet another potential source for SARS-CoV-2 spillover or spillback. At this time, there is no evidence that wildlife are a significant source of SARS-CoV-2 exposure for humans, but the potential for this virus to become established in novel host species could lead to virus evolution in which novel variants may arise. Therefore, continued surveillance of species at risk, such as white-tailed and mule deer, is needed to detect any variants quickly and prevent transmission.

Dr. Porter is a science fellow with the National Wildlife Research Center at the US Department of Agriculture. Her research interests include the pathogenesis and transmission of infectious diseases.

While the significance of SARS-COV-2 susceptibility in mule deer may be slight, the entrenchment of SARS-COV-2 into so many different non-human hosts raises the distinct possibility that - very much like with novel influenza - COVID may evolve and `reinvent' itself in other hosts at irregular intervals, and then spill back into humans.

Since COVID is already well adapted to mammals, it may even be capable of sparking more frequent pandemics than does novel influenza. Time will tell.

The uncomfortable truth is we now live in a new age where the the number, frequency, and intensity of pandemics are only expected to increase over the next few decades (see PNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics).

Which is why we should be preparing seriously now, lest we risk being caught flat-footed and unprepared.

Again.