Credit Nature: Comparative Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2,

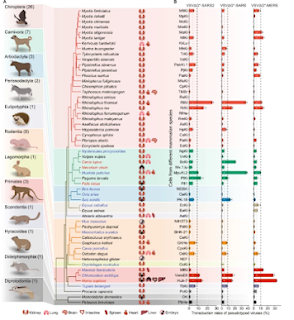

SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV Across Mammals

#18,351

Until the SARS virus began its limited world tour in 2002-2003, (see SARS and Remembrance), only four coronaviruses (Alpha coronaviruses 229E and NL63, and Beta coronaviruses OC43 & HKU1) were known to infect humans.

These human coronaviruses were thought to produce only mild upper respiratory illnesses and were believed responsible for 15%-30% of the `common colds’ around the world, Only rarely did they migrate to the lower respiratory tract (cite).

As of today > 2,600 MERS-related human infections, and 943 associated deaths have been reported, although both are likely under-counts.

SARS-CoV-2, which emerged as COVID-19 five years ago, removed all doubts as to the ability of coronaviruses to spark a major pandemic. And while COVID is exquisitely adapted to humans, it has also shown an unexpectedly broad host range, and has become entrenched in many non-human species.

The concern is - given how rapidly COVID mutates and evolves in humans - it may be undergoing similar parallel evolution in a number of other mammalian species. And at some point, a radically mutated SARS-CoV-2 virus could spill back into the human population.

It is not an idle concern.

In late 2020, Danish authorities announced the spillover of COVID into millions of susceptible farmed mink, and the discovery of several `mink specific' mutations in the virus (see Denmark Orders Culling Of All Mink Following Discovery Of Mutated Coronavirus), which subsequently jumped back into the human population.

Although this `mink variant' was quickly overtaken by the Alpha variant - and no longer circulates - over the summer of 2021 we learned from an SSI Study: Denmark's Cluster-5 mink Variant Had Increased Antibody Resistance.

This served as a `proof of concept' that - if allowed to spread in a non-human species - SARS-CoV-2 could evolve into something `new' and potentially more dangerous, and spillover into the human population with unpredictable results.

Cats and dogs - because they often live in close proximity to humans - are not only at high risk of exposure (see EID Journal: SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence Studies in Pets, Spain) they may also serve as a conduit for the virus to infect other peridomestic animals.

We've seen dozens of other examples of SARS-CoV-2 spilling over into wildlife, including:

Viruses: Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Terrestrial Animals in Southern Nigeria

PNAS: White-Tailed Deer as a Wildlife Reservoir for Nearly Extinct SARS-CoV-2 Variants

All of which brings us to a new report - published last week in Nature - that identifies a short-list of non-human hosts (dogs, cats, mink, deer, etc.) which should be continually monitored for SARS-CoV-2 mutations and specific sites within the Spike Protein that need to be monitored for signs of novel animal variants.

This is a lengthy and detailed report, and I've only posted some brief excerpts. Follow the link to read it in its entirety.

I'll have a postscript after the break.

Article

Open access

Published: 19 October 2024

Study on sentinel hosts for surveillance of future COVID-19-like outbreaksYanjiao Li, Jingjing Hu, Jingjing Hou, Shuiping Lu, Jiasheng Xiong,Yuxi Wang, Zhong Sun,

Weijie Chen, Yue Pan,Karuppiah Thilakavathy, Yi Feng, Qingwu Jiang, Weibing Wang &

Chenglong Xiong

Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 24595 (2024) Cite this articlehttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Abstract

The spread of SARS-CoV-2 to animals has the potential to evolve independently. In this study, we distinguished several sentinel animal species and genera for monitoring the re-emergence of COVID-19 or the new outbreak of COVID-19-like disease. We analyzed SARS-CoV-2 genomic data from human and nonhuman mammals in the taxonomic hierarchies of species, genus, family and order of their host.We find that SARS-CoV-2 carried by domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris), domestic cat (Felis catus), mink (Neovison vison), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) cluster closely to human-origin viruses and show no differences in the majority of amino acids, but have the most positively selected sites and should be monitored to prevent the re-emergence of COVID-19 caused by novel variants of SARS-CoV-2.Viruses from the genera Panthera (especially lion (Panthera leo)), Manis and Rhinolophus differ significantly from human-origin viruses, and long-term surveillance should be undertaken to prevent the future COVID-19-like outbreaks. Investigation of the variation dynamics of sites 142, 501, 655, 681 and 950 within the S protein may be necessary to predict the novel animal SARS-CoV-2 variants.

(SNIP)

Our study highlights the need for a robust One Health-based investigation to monitor susceptible animal hosts. Since the emergence of the COVID-19 epidemic, normal human life and economic activities have been severely disrupted worldwide. It is important to regularly monitor the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in both human and animal populations and to adopt an approach that sustainably balances and optimizes human, animal and ecosystem health to build a community of human health.

(Continue . . . )

While we grudgingly accept that influenza pandemics occur several times a century, and that most have a zoonotic origin, there seems to be a widespread belief that our coronavirus pandemic was somehow a rare - one off - event, that is unlikely to be repeated.

The reality is that coronaviruses are highly mutable, and have the potential to recombine into new variants, which raises concerns over the co-circulation of SARS-CoV-2 along with MERS-CoV, and other coronaviruses (see Nature: CoV Recombination Potential & The Need For the Development of Pan-CoV Vaccines).This despite two other brushes with `COVID-like' epidemics in the past 20 years (SARS & MERS), and the fact that new emerging coronavirus threats continue to be discovered (see J. Med. Virology: Potential Cross-Species Transmission Risks of Emerging Swine Enteric Coronavirus to Human Beings).

Add in the concurrent circulation and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in dozens of other non-human species, and you have ample opportunities for new threats to emerge.

The uncomfortable truth is we now live in a new age where the the number, frequency, and intensity of pandemics are only expected to increase over the next few decades.

BMJ Global: Historical Trends Demonstrate a Pattern of Increasingly Frequent & Severe Zoonotic Spillover EventsPNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics

We can either take that knowledge, and act on it, or wait for the next cascade of events to overwhelm us.