# 10,049

Each month the CDC holds a Grand Rounds web presentation that focuses on a single health-related issue. In the past I’ve highlighted their broadcasts on such diverse topics as Multidrug-Resistant Gonorrhea, Childhood Emergency Preparedness, and Discovering New Diseases . . . to name a few.

The CDC maintains an archive of these informative presentations – going back to 2009 – which you can access at Grand Rounds – Archives. Highly recommended.

With summer almost here, and both Chikungunya and Dengue spreading extensively in the Caribbean and Central and South America, these mosquito borne diseases may be on the verge of making inroads into North America. All of which makes the timing of next week’s presentation fortuitous.

First details on Tuesday’s event, then I’ll be back with more on the arbovirus disease threats to the United States.

Dengue and Chikungunya in Our Backyard: Preventing Aedes Mosquito-Borne Disease

Webcast Links

Windows Media:

http://wm.onlinevideoservice.com/CDC1Flash:

http://www.onlinevideoservice.com/clients/CDC/?mount=CDC3Captions are only available on the Windows Media links. The webcast links are only active during the date and time of the session, but all sessions are archived for future viewing.

Tuesday, May 19 at 1pm EDT

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes are the primary vectors for dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika viruses. Taken together, these viruses account for almost 100 million cases of mosquito-borne disease per year. Globally, dengue is the most important mosquito-borne viral disease. In the last 50 years, incidence has increased 30-fold by expanding into new countries and new areas. Chikungunya often occurs in large outbreaks with high infection rates, affecting more than a third of the population in areas where the virus is circulating. In 2014, more than a million cases were reported worldwide. While Chikungunya disease rarely results in death, the symptoms can be severe and disabling.

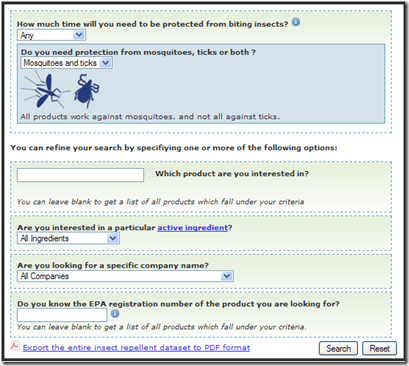

Outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases depend on many factors and are especially difficult to predict, prevent and control. Because there are no licensed vaccines available to prevent dengue or chikungunya, controlling mosquito populations and reducing bites are currently the most effective prevention measures.

This session of Grand Rounds will highlight the importance of preventing Aedes mosquito-borne diseases and the need for improved diagnostic, prevention and control measures.

Presented By:

Marc Fischer, MD, MPH

Chief, Surveillance and Epidemiology Activity, Arboviral Diseases Branch

Division of Vector-Borne Diseases

National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC

"Dengue, Chikungunya and Other Aedes Mosquito-Borne Diseases"Thomas W. Scott, PhD

Professor and Director, Vector-Borne Disease Laboratory

Department of Entomology and Nematology

University of California, Davis

"The Status and Frontiers of Vector Control"Harold Margolis, MD

Branch Chief, Dengue Branch

Division of Vector-Borne Diseases

National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC

"Prevention Strategies for Aedes Mosquito-Borne Diseases"Facilitated By:

John Iskander, MD, MPH, Scientific Director, Public Health Grand Rounds

Phoebe Thorpe, MD, MPH, Deputy Scientific Director, Public Health Grand Rounds

Susan Laird, MSN, RN, Communications Director, Public Health Grand Rounds

Although Dengue and Chikungunya now regularly arrive in the North America via infected (viremic) travelers, we’ve been lucky in that neither has had much success in entrenching itself into our local mosquito populations.

How long our luck will hold is anyone’s guess. West Nile Virus, which emerged in NYC in 1999, quickly spread across the nation and is now a perennial threat.

Chikungunya was introduced by viremic travelers to the Caribbean in the fall of 2013, who inadvertently `seeded’ the virus into the local mosquito population. Over the past 18 months there have been well over 1.4 million infections in the Americas – spanning more than 3 dozen nations - and millions more will undoubtedly be infected in the years to come.

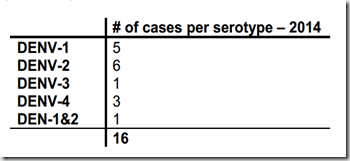

Dengue arrived in South Florida in 2009 in a similar fashion (see MMWR: Dengue Fever In Key West), as did West Nile Virus to NYC in the late 1990s. So far, Dengue and Chikungunya have had only very limited success spreading in the United States. Literally only a handful of cases have been reported thus far.

But as we’ve seen with West Nile Virus - when the right combination of multiple virus introductions, competent vectors, and favorable environmental conditions come together - formerly exotic diseases can get a foothold and even thrive here in the United States.

Right now, Dengue and Chikungunya are minor threats in North America, but that could change quickly. When you add in the other mosquito-borne illnesses (EEE, WNV, SLEV, etc.) it just makes sense to do whatever you can to limit your exposure.

Which is why the Florida State Health Department urge residents and visitors to follow the `5 D’s’: