A busy avian flu season for Europe (prior to Mar. 13th) – Credit Defra

# 9884

On Friday, in Media Reports: Bird Flu Detected In Romania & Italy, we looked at two reported bird flu outbreaks in Europe. The Romanian outbreak – reportedly H5N1 – came on the heels of a similar announcement earlier last week from neighboring Bulgaria.

The outbreak in Italy wasn’t immediately identified, but it follows earlier outbreaks of LPAI H7, LPAI H5, and HPAI H5N8 viruses.

Today we’ve confirmation of both of these outbreaks, and of their subtypes, from separate reports issued by the OIE and the FAO.

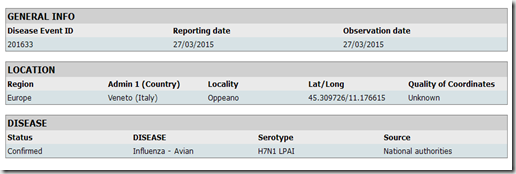

First stop, Italy – where low path (LPAI) H7N1 has been identified on a farm in the Veneto region in the following FAO report.

Of greater concern is an outbreak of HPAI H5N1 in waterfowl around the Danube Delta, as described in the following OIE Report, which describes 64 dead pelicans.

Source of the outbreak(s) or origin of infection

- Unknown or inconclusive

Epidemiological comments

On 25 March, the County Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Directorate (CSVFSD) of Tulcea was notified by the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve Administration (ARBDD) about the identification of 64 carcasses of pelicans in an inhabited area, on Ceaplace island, Sinoe lake. This area is located at the border of Tulcea and Constanta Counties, and no other localities with domestic birds are found on a radius more than 10 km. The entire population of pelicans counted initially more than 250 birds, adults and young. Excluding the dead pelicans (found in different stages of putrefaction), no other birds were observed with clinical signs in the area. Also, in the area were observed other birds species, still unspecified.

After several years of relative quiescence on the bird flu front (at least, outside of China), we are suddenly seeing a remarkable surge in activity, involving several different strains.

H5N1 is not only on the move in migratory birds – showing up in Eastern Europe, and Nigeria after five years absence – it is also raging in poultry in Egypt, and is spilling over into humans this winter at a record rate (see FAO: Egypt’s H5N1 Case Count Continues To Climb).

Meanwhile, the recently emerged H5N8 virus has not only spread across much of Eastern Asia, and into both Europe and North America, it has spawned a number of `local’ reassortant viruses. `New’ versions of H5N2, H5N3, and H5N1 have appeared in Taiwan, and in North America, and already they have had major impacts on the poultry industry in both regions.

And while far less worrisome for now, we’ve also seen an unusual number of low path (LPAI) outbreaks (H5s & H7s) in poultry from Italy, to the UK, to Kansas.

In many ways, the winter of 2014-15 has seen more bird flu activity – over a greater geographic range – than we’ve seen since the great bird flu expansion of 2006, when H5N1 escaped the confines of Asia and barnstormed much of Europe (see H5N8: A Case Of Deja Flu?).

All of which has brought, once again, the role of migratory and wild birds in the spread of these viruses back to the forefront.

While there are still a lot of missing pieces to this puzzle – and outbreaks often appear linked to or exacerbated by the movement of poultry products (legal and illicit), equipment, or personnel – this resurgence in bird flu has brought wild and migratory birds under new scrutiny.

A few recent blogs on the topic include:

Erasmus Study On Role Of Migratory Birds In Spread Of Avian Flu

FAO On The Potential Threat Of HPAI Spread Via Migratory Birds

The North Atlantic Flyway Revisited