Photo Credit- CDC

# 9965

Eleven years ago the Report of the WHO/FAO/OIE Joint Consultation on Emerging Zoonotic Diseases, convened in Geneva, defined an emerging zoonosis as ‘a zoonosis that is newly recognised or newly evolved, or that has occurred previously but shows an increase in incidence or expansion in geographical, host or vector range’

Last year, in Emerging zoonotic viral diseases L.-F. Wang (1, 2) * & G. Crameri wrote:

The last 30 years have seen a rise in emerging infectious diseases in humans and of these over 70% are zoonotic (2, 3). Zoonotic infections are not new. They have always featured among the wide range of human diseases and most, e.g. anthrax, tuberculosis, plague, yellow fever and influenza, have come from domestic animals, poultry and livestock. However, with changes in the environment, human behaviour and habitat, increasingly these infections are emerging from wildlife species.

Patterns that were predicted nearly two decades ago by well respected anthropologist and researcher George Armelagos (May 22, 1936 - May 15, 2014) - of Emory University - who wrote Disease in human evolution: the re-emergence of infectious disease in the third epidemiological transition. National Museum of Natural History Bulletin for Teachers 18(3)

I wrote at some length back in 2011 on The Third Epidemiological Transition, which Dr. Armelagos called the age of re-emerging infectious diseases, a concept he expanded upon in 2010 in The Changing Disease-Scape in the Third Epidemiological Transition, where he wrote:

It is characterized by the continued prominence of chronic, non-infectious disease now augmented by the re-emergence of infectious diseases. Many of these infections were once thought to be under control but are now antibiotic resistant, while a number of “new” diseases are also rapidly emerging. The existence of pathogens that are resistant to multiple antibiotics, some of which are virtually untreatable, portends the possibility that we are living in the dusk of the antibiotic era. During our lifetime, it is possible that many pathogens that are resistant to all antibiotics will appear. Finally, the third epidemiological transition is characterized by a transportation system that results in rapid and extensive pathogen transmission.

In other words, the emergence of MERS-CoV, H5N1, Nipah, Hendra, Lyme Disease, H7N9, H5N6, H10N8, NDM-1, CRE, etc. are not temporary aberrations. They are the new norm, and we should get used to seeing more pathogens like these appear in the coming years.

The emerging infectious diseases are considered such an important threat that the CDC maintains as special division – NCEZID (National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases) – to deal with them. According to the NCEZID:

Emerging means infections that have increased recently or are threatening to increase in the near future. These infections could be

- completely new (like Bourbon virus, which was recently discovered in Kansas or MERS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

- completely new to an area (like chikungunya in Florida).

- reappearing in an area (like dengue in south Florida and Texas).

- caused by bacteria that have become resistant to antibiotics, like MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), C. difficile, or drug-resistant TB.

Over the past 36 months we’ve seen:

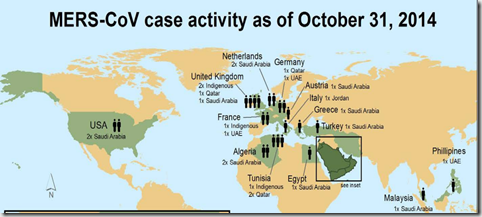

- A novel Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) emerge in the Middle East

- Several new avian flu strains have emerged and jumped to humans, including H7N9, H5N6, H10N8, and H6N1.

- Chikungunya arrived in the Americas, and has already infected well over 1 million people.

- Several new tickborne diseases have emerged (Heartland Virus, Bourbon Virus, SFTS) in the United States and around the world.

- Last summer a new variant of a rarely seen EV-D68 virus swept across the United States, sickening hundreds of thousands of kids and leaving more than 100 paralyzed.

And in the wings we have a number of epizootic diseases – like HPAI H5N2, H5N8, canine H3N2, H10N7 and H3N8 in seals – that while they haven’t jumped to humans, have at least some potential to do so in the future.

Although our awareness of some of these threats is no doubt enhanced by our improved surveillance and testing capabilities, there are reasons to believe the number of zoonotic threats facing us are increasing faster today than we’ve seen in the past.

Additionally, some zoonotic threats – like Lyme disease – are now recognized as being far more prevalent than previously appreciated. In 2013, the CDC revised their Estimate Of Yearly Lyme Disease Diagnoses In The United States, indicating that the number of Lyme Disease diagnoses in the country is probably closer to 300,000 than the 30,000 that are officially reported each year to the CDC.

While exotic diseases have always existed and plagued mankind, never before has mankind been so able to aid and abet their global spread, via our increasingly mobile society.

Chikungunya was undoubtedly introduced by viremic travelers to the Caribbean in the fall of 2013, who inadvertently `seeded’ the virus into the local mosquito population. Since then there have been well over 1.3 million infections in the Americas – spanning more than 3 dozen nations - and millions more will undoubtedly be infected in the years to come.

Presumably Dengue arrived in South Florida in 2009 in a similar fashion, as did West Nile Virus to NYC in the late 1990s. Earlier this year we learned of two travelers who returned to Vancouver infected with the H7N9 virus. A year previously, a nurse died in Alberta, Canada after contracting H5N1 while on a visit to China.

And we’ve seen a handful of Ebola and MERS cases travel via aircraft to the United States, Europe, and the Philippines over the past year.

While vector-borne illnesses like West Nile, Dengue, and Chikungunya have done the best so far, there is really no way to know what the `next big thing’ in global infectious disease spread will be. As the CDC’s Global Health Website puts it:

Why Global Health Security Matters

Disease Threats Can Spread Faster and More Unpredictably Than Ever Before

(Excerpt)

A disease threat anywhere can mean a threat everywhere. It is defined by

- the emergence and spread of new microbes;

- globalization of travel and trade;

- rise of drug resistance; and

- potential use of laboratories to make and release—intentionally or not—dangerous microbes.

A recent Assessment by the Director of National Security (see DNI: An Influenza Pandemic As A National Security Threat) found the global spread of infectious diseases – along with cyber attacks, terrorism, extreme weather events, WMDs, food and water insecurity, and global economic concerns.- constitutes a genuine threat to national security.

As we discussed last year, in The New Normal: The Age Of Emerging Disease Threats, the reality of life in this second decade of the 21st century is that disease threats that once were local, can now spread globally in a matter of hours or days.

We’ve been lulled into a false sense of security since the last pandemic was relatively mild, and the feeling is they only come around every 30 or 40 years. But viruses don’t read calendars, or play by `mostly likely worst-case scenario rules’ that are adopted by most planning committees.

The time has come to take pandemic planning seriously again, not because of one specific threat like MERS or H5N1, but because there’s a growing list of pathogens with pandemic potential queuing up around the globe.

All of which makes this a good time for agencies, organizations, businesses, communities, and families to dust off their pandemic plans, review them, and make any needed refinements.

You do have a pandemic plan, don’t you?

For some recent pandemic preparedness blogs, you may wish to revisit:

Do You Still Have A CPO?

Pandemic Planning For Business

NPM13: Pandemic Planning Assumptions

The Pandemic Preparedness Messaging Dilemma