Photo Credit CDC PHIL

# 6936

Very early in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic we began to see reports (see H1N1 Morbidity And Previously Existing Conditions) of unusual numbers of obese influenza patients populating intensive care facilities around the world, raising concerns that obesity might be a significant pandemic risk factor.

In her address to the world announcing the declaration of the H1N1 pandemic on June 11th, (see WHO: Chan Statement On Raising Pandemic Level), Margaret Chan listed obesity as one of the pre-existing conditions that lent themselves to severe outcomes with this virus, saying:

“Many, though not all, severe cases have occurred in people with underlying chronic conditions. Based on limited, preliminary data, conditions most frequently seen include respiratory diseases, notably asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and obesity.”

Over the next couple of months obesity, and particularly morbid obesity, was frequently mentioned as a possible risk factor, along with asthma, diabetes, and immune disorders.

That is, until an ACIP meeting held at the end of July, where evidence was presented that showed that the incidence of hospitalizations among those listed as obese by their BMI was practically the same as their prevalence in society.

Roughly 34% of Americans are obese, and roughly 38% of those hospitalized met that criteria. While 6% are morbidly obese (BMI > 40), they only made up 7% of the hospitalized cases.

At the time the CDC’s Dr. Anne Schuchat stated that the jury was still out on the morbidly obese, but there was no clear evidence that obesity – without some comorbid condition like diabetes – created a greater risk of complications from pandemic H1N1.

Of course, this was very early in the game, and data was sparse.

In September, in Study: Half Of ICU H1N1 Patients Without Underlying Conditions, it became apparent that while pre-existing risk factors were important, they were not the sole reason behind flu victims ending up in intensive care.

In November, Eurosurveillance Journal published a Study: H1N1 Hospitalization Profiles, that similarly found :

- The most common risk factor in admission to intensive care was chronic respiratory disease followed by chronic neurological disease, asthma and severe obesity.

- 51% of hospitalized cases and 42% of ICU cases were not in a recognized risk group.

This back-and-forth reporting on the significance of obesity as a risk factor continued, which I covered in blogs including:

NIH: Post Mortem Studies Of H1N1

Study: Quantifying H1N1 Risk Factors

Morbid Obesity And H1N1 Flu

In March of 2010, the CDC (in response to a recently published PLoS One study), posted the following:

What has been learned from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic about obesity and risk of serious influenza disease death?

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, early reports from the United States and abroad suggested that obesity was more frequent among persons hospitalized with 2009 H1N1 disease or who died following 2009 H1N1 infection.

Since that time, a number of studies have suggested that many 2009 H1N1patients tend to be morbidly obese. The study “Morbid Obesity as a Risk Factor for hospitalization and Death due to 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Disease,” published in PLoS ONE, sought to determine whether or not obesity or morbid obesity were in fact independent risk factors for serious 2009 H1N1-related complications, including death. This study found that morbidly obesity persons have a higher risk of hospitalization for 2009 H1N1 infection compared to persons with normal weight. Data from this study also suggest that the risk of death following H1N1 infection may be higher for morbidly obese individuals.

As more data was gathered analyzed, it was becoming apparent that morbid obesity (BMI > 40) was associated with a greater risk from pandemic flu.

In early 2011 (see Extreme Obesity: A Novel Risk Factor For A Novel Flu) the IDSA’s journal Clinical Infectious Diseases carried a study called A Novel Risk Factor for a Novel Virus: Obesity and 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1), that found:

Extreme obesity associated with higher risk of death for 2009 H1N1 patients

[EMBARGOED FOR JAN. 5, 2011] For those infected with the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus, extreme obesity was a powerful risk factor for death, according to an analysis of a public health surveillance database. In a study to be published in the February 1, 2011, issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases, researchers associated extreme obesity with a nearly three-fold increased odds of death from 2009 H1N1 influenza. Half of Californians greater than 20 years of age hospitalized with 2009 H1N1 were obese.

All of which serves as prelude to a new study that appears in PLoS One today called:

Viral Pneumonitis Is Increased in Obese Patients during the First Wave of Pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 Virus

Jen Kok, Christopher C. Blyth, Hong Foo, Michael J. Bailey, David V. Pilcher, Steven A. Webb, Ian M. Seppelt, Dominic E. Dwyer, Jonathan R. Iredell

Introduction

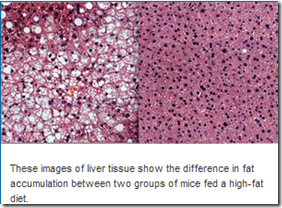

There is conflicting data as to whether obesity is an independent risk factor for mortality in severe pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza (A(H1N1)pdm09). It is postulated that excess inflammation and cytokine production in obese patients following severe influenza infection leads to viral pneumonitis and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Methods

Demographic, laboratory and clinical data prospectively collected from obese and non-obese patients admitted to nine adult Australian intensive care units (ICU) during the first A(H1N1)pdm09 wave, supplemented with retrospectively collected data, were compared.

Results

Of 173 patients, 100 (57.8%), 73 (42.2%) and 23 (13.3%) had body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2 (obese) and ≥40 kg/m2 (morbidly obese) respectively.

Compared to non-obese patients, obese patients were younger (mean age 43.4 vs. 48.4 years, p = 0.035) and more likely to develop pneumonitis (61% vs. 44%, p = 0.029).

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use was greater in morbidly obese compared to non-obese patients (17.4% vs. 4.7%, p = 0.04). Higher mortality rates were observed in non-obese compared to obese patients, but not after adjusting for severity of disease.

C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and hospital length of stay (LOS) were similar. Amongst ICU survivors, obese patients had longer ICU LOS (median 11.9 vs. 6.8 days, p = 0.017). Similar trends were observed when only patients infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 were examined.

Conclusions

Among patients admitted to ICU during the first wave of A(H1N1)pdm09, obese and morbidly obese patients with severe infection were more likely to develop pneumonitis compared to non-obese patients, but mortality rates were not increased. CRP is not an accurate marker of pneumonitis.

Interestingly, what these researchers found was a mixed bag. While obesity was linked to a higher incidence of pneumonitis, somewhat surprisingly it was not linked to a higher rate of mortality.

The authors write:

In the present study, obesity was an independent predictor of pneumonitis after adjusting for age and chronic lung disease. Furthermore, clinicians may have intervened with more advanced levels of respiratory support in the obese patients pre-emptively and more readily prior to even more significant respiratory failure.

Although our obese patients were more likely to develop pneumonitis, they were also more likely to recover once the acute lung insult resolved.

The duration of mechanical ventilation was similar between obese and non-obese patients, comparable to the experience of critically ill patients with respiratory failure prior to the 2009 pandemic

The entire research article is very much worth reading, but the authors end by writing:

In conclusion, obese patients with severe A(H1N1)pdm09 infection from the first pandemic wave in Australia were more likely to develop pneumonitis compared to non-obese patients, but mortality rates were similar between the two groups after adjusting for severity of disease.

Although there is on-going debate as to whether obesity is a risk factor for severe A(H1N1)pdm09 infection, annual influenza vaccination should be prioritized in this group given the increased risk of serious complications from seasonal influenza infection

Nearly 4 years after the initial outbreak of novel H1N1, research on this most-studied pandemic of all time continues. The massive amount of data collected during the 2009-2012 pandemic has not yet been fully explored, and will undoubtedly fuel many more studies for years to come.