#17,151

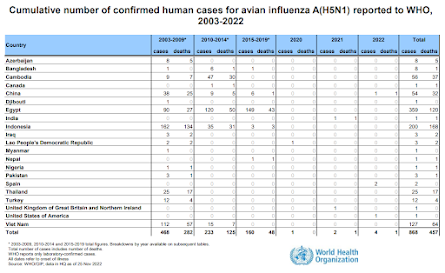

Although only a handful of extremely mild human infections have been reported with this current strain (clade 2.3.4.4b) of H5N1, other - closely related clades - have infected hundreds of people over the past 20 years, often with fatal results.

Over that time we've seen clusters of cases, and mini-epidemics, in a number of countries (Vietnam, China, Indonesia, Cambodia, Egypt, etc.). But after months - or sometimes years - the virus has lost its punch, likely mutating slightly into a less `humanized' strain.

But mutations are random, and there is no reason to suspect that another reassortment, or the right combination of amino acid changes due to antigenic drift - or both - couldn't turn our current H5N1 virus into something more formidable.

Two weeks ago, in Preprint: Rapid Evolution of A(H5N1) Influenza Viruses After Intercontinental Spread to North America, we looked at the mammalian adaptations occurring in avian H5N1 as it spread across the US and Canada, producing serious - often fatal - infections in mink, bears, foxes, seals, and other small terrestrial mammals.

As H5N1 moves into South America (see map below), it will have even more opportunities to mutate, adapt, and evolve. While it doesn't guarantee the virus will continue to evolve toward becoming a bigger threat, it is a possibility that public health agencies can't afford to ignore.

HPAI H5 isn't the only other pandemic threat out there (think: MERS-CoV, Swine EA H1N1 `G4', new COVID variants, among others), but it is making enough noise around the world to have raised concerns.

Yesterday PAHO (Pan-American Health Organization) updated their earlier (Nov 19th) Epidemiological Alert on H5N1, warning:

Given the increase in outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza in poultry farms, backyards, and wild birds in countries of the Region of the Americas and other Regions, the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) recommends that the Member States strengthen coordination between sectors involved in alerting and responding to zoonotic events and implement the necessary measures to contain emerging pathogens that may put public health at risk. PAHO/WHO recommends monitoring the occurrence of influenza-like illness (ILI) or severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) in people exposed to birds (domestic, wild, or in captivity) infected with influenza viruses

The updated 11-page PDF provides summaries of H5N1 activity in the United States, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, and then provides recommendations for health authorities in member states.

Epidemiological Update3 December 2022

(Excerpt)

Recommendations for health authorities in Member States

Both HPAI and LPAI viruses can be rapidly spread among poultry through direct contact with infected waterfowl or other poultry, or through direct contact with fomites or surfaces, or water contaminated with the viruses. Infection of poultry with HPAI viruses can cause severe disease with high mortality. LPAI viruses are more associated with subclinical infection. The terms HPAI and LPAI apply only to the symptoms in birds (chickens in particular), and both types of viruses have the potential to cause infections in humans.

While the potential exists for these viruses to cause human infections, infections with avian influenza viruses are generally rare and when they have occurred, these viruses have not spread easily from person-to-person. To date, no person-to-person human transmission caused by avian influenza A(H5N8), A(H5N2), or A(H5N1) viruses has been reported either in the Americas or globally.

Intersectoral coordination

Control of the disease in animals is the first measure to reduce the risk to humans. For this reason, it is important that prevention and control actions, both in the animal and human health sectors, are carried out in a coordinated and concerted manner. Agile information exchange mechanisms will have to be established and/or strengthened to facilitate coordinated decision - making.

Implementation of a comprehensive surveillance program, including wild birds and both backyard and commercial poultry, is essential. Targeted risk-based surveillance strategies should be combined with a strengthening of general surveillance. In this regard, sensor awareness tasks are key, particularly in the backyard, to encourage the detection and notification of suspicious events. These programs also provide information that enables spread modeling and more accurate risk analysis.

Full recommendations for strengthening intersectoral work on surveillance, early detection, and investigation of influenza events at the human-animal interface are available at: https://bit.ly/3glEUNN

Surveillance in humans

People at risk of contracting infections are those directly or indirectly exposed to infected birds, for example, poultry keepers who maintain close and regular contact with infected birds or during slaughter or cleaning and disinfection of affected farms. For this reason, the use of adequate personal protective equipment and other protection measures is recommended to avoid zoonotic transmission in these operators.

In order to identify early transmission events at the human-animal interface, surveillance of exposed persons is recommended. In this sense, it is recommended to monitor the appearance of influenza-like illness (ILI) or severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) in people exposed to birds (domestic, wild, or in captivity) infected with influenza viruses during zoonotic events.

Given the detection of an infection in humans, early notification is essential for an investigation and implementation of adequate measures that include the early isolation and treatment of the case, the active search for other cases associated with the outbreak, as well as the identification of close contacts for management and follow-up (11).

Health personnel in areas where transmission of avian influenza (HPAI or LPAI) in birds is taking place should be alerted about the possibility of infection in people exposed to these viruses.

PAHO/WHO reiterates to Member States the need to maintain influenza virus surveillance and to immediately ship human influenza samples to the US CDC WHO Collaborating Center.

There is still some debate over whether H5 viruses can spark a human epidemic (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?), but by the time we have a definitive answer to that, we could be hip-deep in cases.

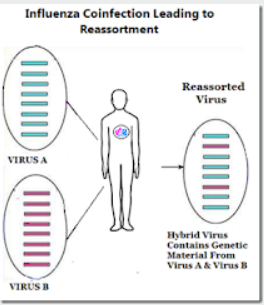

But even if it requires an H1, H2, or H3 virus to really take off in humans, a co-infection between human seasonal (H1N1 or H3N2) and an avian or swine flu virus could produce an enhanced seasonal virus.

Reassortment isn't just for the birds.

That virus was a reassortment consisting of 2 genes from a low path avian influenza H3 virus, and 6 genes from H2N2. And while it was not initially as deadly as the 1957 or 1918 pandemics - it is still with us 54 years later - and has caused millions of additional deaths over the past half century.

Which is why - as tired as we are of dealing with COVID - we can't afford to sit back and ignore the rise of H5N1 (or any other novel flu virus).

Given how often it has happened before, we can be pretty sure it will happen again. We just don't know where, when, or how bad it will be.