#17,205

While the world is understandably preoccupied with the ongoing COVID pandemic, a `new and improved' avian H5N1 virus is making its way around the world - killing millions of birds - and infecting the occasional mammal (see here, here, here, and here), including a handful of humans.

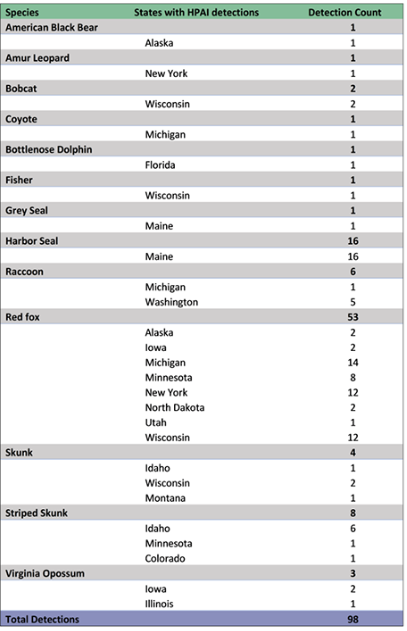

Foxes and seals have been the most commonly reported mammals to be infected by our current wave of HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, but most animal deaths in the wild are never reported, and so our perception of H5N1's impact on non-avian wildlife is likely significantly under-estimated.

The USDA's list of mammalian species affected (below) in the United States is far from complete, and continues to expand. Most are carnivores, or scavengers, who likely fed on an infected bird carcass.

We'v seen similar reports from Europe, and the UK, as well with this virus. This week France filed a report with WOAH (World Organization for Animal Health) on the discovery of an H5N1 infected cat on a poultry farm in western France.

The cat tested positive for the virus, and was euthanized, according to the brief epidemiological note accompanying the report (`Cat present in a poultry farm (HPAI outbreak ob-110288, event 4116). The animal was euthanized on December 23rd.').

Up until about 20 years ago, cats (and dogs) were thought largely immune to flu. That perception abruptly changed in 2003-2004 when large cats (mostly tigers) kept in Asian zoos began to die after being feed H5N1 infected raw chicken, and dogs in Florida became infected with H3N8 equine flu.

The following comes from a World Health Organization GAR report from 2006.

H5N1 avian influenza in domestic cats

28 February 2006

(EXCERPTS)

Several published studies have demonstrated H5N1 infection in large cats kept in captivity. In December 2003, two tigers and two leopards, fed on fresh chicken carcasses, died unexpectedly at a zoo in Thailand. Subsequent investigation identified H5N1 in tissue samples.

In February 2004, the virus was detected in a clouded leopard that died at a zoo near Bangkok. A white tiger died from infection with the virus at the same zoo in March 2004.

In October 2004, captive tigers fed on fresh chicken carcasses began dying in large numbers at a zoo in Thailand. Altogether 147 tigers out of 441 died of infection or were euthanized. Subsequent investigation determined that at least some tiger-to-tiger transmission of the virus occurred.

In 2007, Dr. C.A. Nidom demonstrated that of 500 cats he tested in and around Jakarta, 20% had antibodies for the bird flu virus. In 2007 the FAO warned that: Avian influenza in cats should be closely monitored, and in 2012 the OIE reported on Cats Infected With H5N1 in Israel,

Perhaps the best investigated case was an outbreak of avian H7N2 among hundreds of cats across several NYC animal shelters, where at least two employees were infected (see J Infect Dis: Serological Evidence Of H7N2 Infection Among Animal Shelter Workers, NYC 2016), while 5 others exhibited low positive titers to the virus, indicating possible infection.Since then we've seen numerous reports of cats infected with H5N1, H5N6, H7N2, H9N2, and H3N8 avian flu viruses. And in a very few instances, we've seen reports of suspected, or sometimes probable, transmission from cats to humans.

Although cat-to-human transmission of influenza remains very rare, you'll find other examples here, and here. And while not influenza, last summer we also saw EID Journal: Suspected Cat-to-Human Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 - Thailand.

Companion animals, particularly those who have a life outside of the household, are in a unique position to transmit zoonotic viruses from the wild to humans. Although the risks are low, we've seen instances of cats transmitting plague, or bovine TB to their owners, and with H5N1 showing up increasingly in our environment the CDC has some updated advice for pet owners.

Although bird flu viruses mainly infect and spread among wild migratory water birds and domestic poultry, some bird flu viruses can infect and spread to other animals as well. Bird flu viruses have in the past been known to sometimes infect mammals that eat (presumably infected) birds or poultry, including but not limited to wild animals such as foxes and skunks; stray or domestic animals such cats and dogs; and zoo animals such as tigers and leopards.

While it’s unlikely that people would become infected with bird flu viruses through contact with an infected wild, stray, feral, or domestic mammal, it is possible—especially if there is prolonged and unprotected exposure to an infected animal. This page provides information for different groups of people who might have direct contact with infected or potentially infected sick or dead animals, including animals that might have eaten or been exposed to bird flu-infected birds.

Pet Owners

If your domestic animals (e.g., cats or dogs) go outside and could potentially eat or be exposed to sick or dead birds infected with bird flu viruses, or an environment contaminated with bird flu virus, they could become infected with bird flu. While it’s unlikely that you would get sick with bird flu through direct contact with your infected pet, it is possible. For example, in 2016, the spread of bird flu from a cat to a person was reported in NYC. The person who was infected [2.29 MB, 4 pages] was a veterinarian who had mild flu symptoms after prolonged exposure to sick cats without using personal protective equipment.

If your pet is showing signs of illness compatible with bird flu virus infection and has been exposed to infected (sick or dead) wild birds/poultry, you should monitor your health for signs of fever or infection.

Take precautions to prevent the spread of bird flu.

As a general precaution, people should avoid direct contact with wild birds and observe wild birds only from a distance, whenever possible. People should also avoid contact between their pets (e.g., pet birds, dogs and cats) with wild birds. Don’t touch sick or dead birds, their feces or litter, or any surface or water source (e.g., ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with their saliva, feces, or any other bodily fluids without wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). More information about specific precautions to take for preventing the spread of bird flu viruses between animals and people is available at Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People. Additional information about the appropriate PPE to wear is available at Backyard Flock Owners: Take Steps to Protect Yourself from Avian Influenza.

People Who Have Had Direct Contact with Infected or Potentially Infected Animals

During outbreaks of bird flu in wild birds and/or poultry, people who have had direct contact with infected or potentially infected animals, including sick animals that might have eaten bird flu-infected birds, should monitor their health for fever and symptoms of infection.

- Signs and Symptoms may include: Fever (Temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) or feeling feverish/chills*Cough

- Sore throat

- Difficulty breathing/Shortness of breath

- Conjunctivitis (eye tearing, redness, irritation, or discharge from eye)

- Headaches

- Runny or stuffy nose

- Muscle or body aches

- Diarrhea

*Fever may not always be present

Call your state/local health department immediately if you develop any of these signs or symptoms during the 10-days after your exposure to an infected or potentially infected animal. Discuss your potential exposure and ask about testing. If testing is recommended, isolate as much as possible until test results come back and/or you have recovered from your illness.

Additionally, close contacts (family members, etc.) of people who have been exposed to a person or animal with lab-confirmed bird flu viruses should also monitor their health for 10 days after their exposure for signs and symptoms of illness. If close contacts of people who have been exposed to H5 bird flu viruses develop signs and symptoms of illness, they should also contact their state health department.

Admittedly, we've stood on the viral precipice before with avian H5N1 (primarily in Indonesia and Egypt), and H7N9 (in China), and each time the threat has receded.

But past failures are no guarantee that some future incarnation of H5N1 won't have the `right stuff' to spark a pandemic.

So we follow all reports of spillover of this avian virus to mammals with considerable interest.