# 5543

There’s an old story about a guy who fears his wife may be cheating on him, so he he hires a private detective to follow her.

A couple of days later the detective brings him pictures of her meeting with a strange man in a bar, driving together to a sleazy motel, and the two of them going into a rented room and pulling the shades.

The husband sighs and says, “Always that element of doubt . . . ”

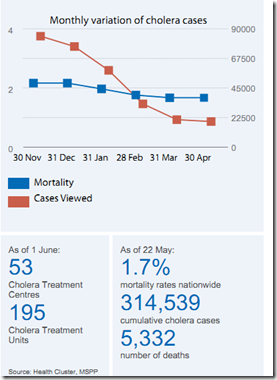

Which pretty much sums up the recent UN report on the origins of Haiti’s Cholera outbreak, which has killed nearly 5,000 individuals (a story well reported by Crof) and sickened a quarter of a million.

Source – OCHA as of April 25th, 2011

The report acknowledged:

- Haiti had been free of cholera for decades

- The strain that showed up in October was closely matched to the strains found in Southeast Asia, including Nepal

- That Nepali peacekeepers (MINUSTAH) arrived in Mirebalais shortly before the outbreak began

- The sanitation conditions at the Mirebalais MINUSTAH camp were not sufficient to prevent contamination of the Meye Tributary System with human fecal waste.

The report further admits that Cholera was undoubtedly introduced by someone visiting from Southeast Asia.

The evidence does not support the hypotheses suggesting that the current outbreak is of a natural

environmental source. In particular, the outbreak is not due to the Gulf of Mexico strain of Vibrio cholerae, nor is it due to a pathogenic mutation of a strain indigenously originating from the Haitian environment.

Instead, the evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that the source of the Haiti cholera

outbreak was due to contamination of the Meye Tributary of the Artibonite River with a pathogenic

strain of current South Asian type Vibrio cholerae as a result of human activity.

They conclude, however by saying that:

The precise country from where the Haiti isolate of Vibrio cholerae O1 arrived is debatable.

Preliminary genetic analysis using MLVA profiles and cholera toxin B subunit mutations indicate that the strains isolated during the cholera outbreak in Haiti and those circulating in South Asia, including Nepal, at the same time in 2009-2010 are similar.

Always that element of doubt.

The UN report goes on to reference 9 factors that contributed to the outbreak – mostly relating to poor sanitary conditions in Haiti, a lack of immunity, and the virulence of the strain – and then states:

The Independent Panel concludes that the Haiti cholera outbreak was caused by the confluence of circumstances as described above, and was not the fault of, or deliberate action of, a group or individual.

The source of cholera in Haiti is no longer relevant to controlling the outbreak. What are needed at this time are measures to prevent the disease from becoming endemic.

Incongruously, while painting a picture that strongly suggests the Nepali troops were a likely source of the outbreak, this UN report goes to great lengths not to state it as actual fact.

In fairness, it is probably impossible to know – with absolute certainty – whether the Nepali peacekeepers brought cholera into Haiti. The evidence may be strong, but it is circumstantial.

Which, frankly, describes the data from most epidemiological investigations.

Obviously this is a diplomatic hot potato, and this UN report does what it can to try to move forward, rather than assign blame.

And one can certainly sympathize with the MINUSTAH troops – there to do humanitarian work in a difficult environment with primitive sanitary facilities – who may have inadvertently (and unknowingly) introduced cholera into the country.

As the saying goes, `No good deed goes unpunished’.

This week we’ve a another report (published online ahead of print) from the CDC’s EID Journal which is a bit more direct in its assessments.

Piarroux R, Barrais R, Faucher B, Haus R, Piarroux M,

Gaudart J, et al. Understanding the cholera epidemic, Haiti. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Jul; [Epub ahead of print]

Abstract (Excerpts)

After onset of the cholera epidemic in Haiti in mid-October 2010, a team of researchers from France and Haiti implemented field investigations and built a database of daily cases to facilitate identification of communes most affected.

Several models were used to identify spatio-temporal clusters, assess relative risk associated with the epidemic’s spread, and investigate causes of its rapid expansion in Artibonite Department.

<SNIP>

Our findings strongly suggest that contamination of the Artibonite and 1 of its tributaries downstream from a military camp triggered the epidemic.

You’ll find a detailed analysis of the outbreak and its spread in this paper, along with arguments that asymptomatic carriers of cholera would have been unlikely to shed enough V. cholerae in their stools to have sparked the outbreak.

They believe that at some point, `symptomatic cases occurred inside the MINUSTAH camp’. A point that, to my knowledge, has never been conceded by the Nepali contingent.

From the Discussion section the authors give their rationale for the importance of determining the origin of the outbreak:

Determining the origin and the means of spread of the cholera epidemic in Haiti was necessary to direct the cholera response, including lasting control of an indigenous bacterium and the fight for elimination of an accidentally imported disease, even if we acknowledge that the latter might secondarily become endemic.

Putting an end to the controversy over the cholera

origin could ease prevention and treatment by decreasing the distrust associated with the widespread suspicions of a cover-up of a deliberate importation of cholera (15,16).

Demonstrating an imported origin would additionally compel international organizations to reappraise their procedures. Furthermore, it could help to contain disproportionate fear toward rice culture in the future, a phenomenon responsible for important crop losses this year (17).

Notably, recent publications supporting an imported origin (7) did not worsen social unrest, contrary to what some dreaded (18–20).

Our epidemiologic study provides several additional arguments confirming an importation of cholera in Haiti.

There was an exact correlation in time and places between the arrival of a Nepalese battalion from an area experiencing a cholera outbreak and the appearance of the first cases in Meille a few days after.

The remoteness of Meille in central Haiti and the absence of report of other incomers make it unlikely that a cholera strain might have been

brought there another way.

An accompanying editorial appears (Dowell SF, Braden CR. Implications of the introduction of cholera to Haiti. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Jul; [Epub ahead of print]))

It states, in part:

For Haiti, the future course of the cholera epidemic is difficult to predict, especially given the chronic degradation of water and sanitation infrastructure over many years and the acute disruption from the earthquake in Haiti in January 2010 (6).

Improving water and sanitation infrastructure is clearly the most effective and lasting approach to prevent the spread of cholera in countries where it is endemic as well as in those that are currently cholera-free.

Simple enough sounding solutions, but terribly difficult to implement in an impoverished, earthquake wracked, and dysfunctional nation like Haiti.