# 9922

During late June of 2012 we saw the first report in nearly 2 decades of an HPAI in Mexico (see Mexico: High Path H7 In Jalisco), an outbreak that quickly spread among neighboring poultry farms, leading Mexico To Declare a National H7N3 Animal Health Emergency in early July.

During the next few months 22 million birds either died from the virus, or were culled to prevent its spread. Sporadic outbreaks continued well into the summer of 2013 (see OIE report Follow-up report No. 11).

Beyond the massive economic damage to the poultry industry, we also saw a couple of mild human infections with the virus (see MMWR: Mild H7N3 Infections In Two Poultry Workers - Jalisco, Mexico), resulting in conjunctivitis without fever or respiratory symptoms.

At that time – and this was before the emergence of H7N9 in China – H7 viruses were regarded as a big problem for the poultry industry, but not really much of a threat to human health. We’d seen a handful of H7 infections (H7N7, H7N2, H7N3) in humans over the years, but almost always with mild symptoms:

- In 2003 a large outbreak of H7N7 (89 confirmed, 1 fatality) in the Netherlands – with nearly all reported cases having very mild (often just conjunctivitis) symptoms.

- The Fraser Valley H7N3 outbreak of 2004 resulted in at least two human infections, as reported in this EID Journal report: Human Illness from Avian Influenza H7N3, British Columbia

- In 2006 1 person in the UK was confirmed to have contracted H7N3, and the following year, 4 people tested positive for H7N2 – both following local outbreaks in poultry.

The emergence of a highly pathogenic (in people, not birds) H7N9 has put H7 viruses back in the limelight, but for now there are no indications that any of the other H7 strains pose a serious human health risk. That said, viruses continue to evolve and change, and what we can say about a particular subtype today may not hold true forever.

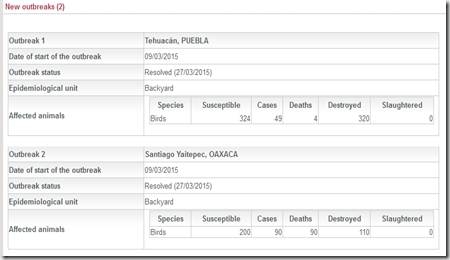

All of which serves as prelude for an OIE Notification today out of Mexico of two H7N3 outbreaks in backyard flocks in the southern states of Oaxaca and of Puebla. There is no known epidemiological link between these two sites at this time, and the good news is both detections were in small backyard holdings, not in large commercial operations.

Source of the outbreak(s) or origin of infection

- Unknown or inconclusive

Epidemiological comments

Following the notification by the owners of an increase in sudden death in birds at two backyards located in the States of Oaxaca and of Puebla, animals showing clinical signs suggestive of avian influenza were identified in both outbreaks. The official veterinary services launched the necessary epidemiological investigation and the presence of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus subtype H7N3 was confirmed. Control measures implemented immediately are, among others: quarantine, movement restrictions, stamping out and sampling in the focal and perifocal areas. Both outbreaks were confirmed as positive for avian influenza on 9 March and later by determining the intravenous pathogenicity index. So far, no epidemiological link has been identified between them.

While seemingly a minor incident - in this year of rapidly expanding avian flu – it is worth taking note of all H5 and H7 outbreaks, regardless of their size.