How viruses shuffle their genes (reassort)

# 9763

In the `Good Old Days’ – that is, before the spring of 2013 – the bird flu threat around the world was pretty much centered around the H5N1 virus, which re-emerged in 2003 after making a brief appearance in the mid-1990s in Hong Kong and Southern China.

Sure, there were some `minor’ players – primarily H7 viruses and H9N2 – that had shown the ability to infect humans on rare occasions, but they only tended to produce mild illness, and were pretty far down the threat list.

The one we worried about most was H5N1 – or rather, the many clades of H5N1 – as the virus is constantly evolving, reinventing itself as it traveled through hosts and around the world. While we often talk about H5N1 as a single threat, in truth it encompasses a growing array of viruses, with considerable variability in each strain’s ability to infect, and kill (see Differences In Virulence Between Closely Related H5N1 Strains).

(click to load larger image) (Note: Chart only goes through 2011)

Quite simply, the clade of H5N1 circulating in Cambodia is genetically different from the clade in Indonesia, or Egypt. And within each of these clades there are constantly evolving variants.

By the winter of 2013 H5N1 had infected in excess of 600 people, killing roughly 60% of known cases.

But on March 31st of 2013 we learned of a new dangerous player in the bird flu world, and unexpectedly it emerged from the H7 camp, which previously had only produced mildly pathogenic (in humans) viruses. The H7N9 virus appeared in China, and in two short months infected at least 134 people, killing about 1/3rd.

Although H5N1 didn’t go away, it did recede from the limelight as H7N9 quite impressively managed to infect as many people in its first 24 months as H5N1 was known to have infected in its first 10 years.

Credit Dr. Ian Mackay’s VDU Blog

After a decade of monolithic concerns, we had two serious avian flu threats to contend with.

But within a matter of months we would see that roster expand to include H5N2, H5N3, H5N6, H5N8, and H10N8.

While H5N2 and H5N8 have not (as yet) proved to be a human health threat, they are viewed with caution as they continue to evolve, and are closely related to viruses that do (see CDC Interim Guidance For Testing For Novel Flu).

Over the past four months we’ve watched a remarkable resurgence of H5N1 in both poultry and humans in Egypt, with 108 human infections reported over the past 120 days (see WHO Releases Updated Egyptian H5N1 Numbers).

This is now the biggest sustained run of human H5N1 cases in one country since the virus appeared in 2003, and it shows little signs of abating any time soon.

While we still watch H7N9 closely for signs that it is becoming more easily transmitted among humans - and we keep close watch on these other new subtypes - H5N1 is back on top of our avian flu watch list, as last night’s announcement from the World Health Organization (see WHO Warns On Evolving Influenza Threat) attests.

(excerpt)

H5 viruses: currently the most obvious threat to health

The highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus, which has been causing poultry outbreaks in Asia almost continuously since 2003 and is now endemic in several countries, remains the animal influenza virus of greatest concern for human health. From end-2003 through January 2015, 777 laboratory-confirmed human cases of H5N1 virus infection have been reported to WHO from 16 countries. Of these cases, 428 (55.1%) have been fatal.

Over the past two years, H5N1 has been joined by newly detected H5N2, H5N3, H5N6, and H5N8 strains, all of which are currently circulating in different parts of the world. In China, H5N1, H5N2, H5N6, and H5N8 are currently co-circulating in birds together with H7N9 and H9N2.

The H9N2 virus has been an important addition to this mix, as it served as the “donor” of internal genes for the H5N1 and H7N9 viruses. Over the past four months, two human infections with H9N2 occurred in China. Both infections were mild and the patients fully recovered.

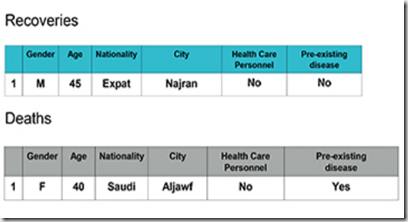

Virologists interpret the recent proliferation of emerging viruses as a sign that co-circulating influenza viruses are rapidly exchanging genetic material to form novel strains. Viruses of the H5 subtype have shown a strong ability to contribute to these so-called “reassortment” events.

The genomes of influenza viruses are neatly segmented into eight separate genes that can be shuffled like playing cards when a bird or mammal is co-infected with different viruses. With 18 HA (haemagluttinin) and 11 NA (neuraminidase) subtypes known, influenza viruses can constantly reinvent themselves in a dazzling array of possible combinations. This appears to be happening now at an accelerated pace.

For example, H5N2 viruses recently detected in poultry in Canada and in wild birds in the US are genetically different from H5N1 viruses circulating in Asia. These viruses have a mix of genes from a Eurasian H5N8 virus, likely introduced into the Pacific Flyway in late 2014, along with genes from North American influenza viruses.

Little is known about the potential of these novel viruses to infect humans, but some isolated human infections have been detected. For example, the highly pathogenic H5N6 virus, a novel reassortant, was first detected at a poultry market in China in March 2014. The Lao People’s Democratic Republic reported its first outbreak in poultry, also in March, followed by Viet Nam in April. Genetic studies showed that the H5N6 virus resulted through exchange of genes from H5N1 viruses and H6N6 viruses that had been widely circulating in ducks.

China detected the world’s first human infection with H5N6, which was fatal, in April 2014, followed by a second severe human infection in December 2014. On 9 February 2015, a third human H5N6 infection, which was fatal, was reported.

The emergence of so many novel viruses has created a diverse virus gene pool made especially volatile by the propensity of H5 and H9N2 viruses to exchange genes with other viruses. The consequences for animal and human health are unpredictable yet potentially ominous.

(Continue . . .)

Although not a major threat in itself, H9N2 appears instrumental in the creation of new, dangerous H5 reassortant viruses (see PLoS Path: Genetics, Receptor Binding, and Transmissibility Of Avian H9N2). This ubiquitous, yet fairly benign avian virus is quite promiscuous, as we keep finding bits and pieces of it turning up in new reassortant viruses

Of the H5 avian flu viruses we are currently watching with the greatest concern – all share several important features (see Study: Sequence & Phylogenetic Analysis Of Emerging H9N2 influenza Viruses In China):

- They all first appeared in Mainland China

- They all have come about through viral reassortment in poultry

- And most telling of all, while their HA and NA genes differ - they all carry the internal genes from the avian H9N2 virus

In January of 2014, The Lancet carried a report entitled Poultry carrying H9N2 act as incubators for novel human avian influenza viruses by Chinese researchers Di Liu a, Weifeng Shi b & George F Gao that warned:

Several subtypes of avian influenza viruses in poultry are capable of infecting human beings, and the next avian influenza virus that could cause mass infections is not known. Therefore, slaughter of poultry carrying H9N2—the incubators for wild-bird-origin influenza viruses—would be an effective strategy to prevent human beings from becoming infected with avian influenza.

We call for either a shutdown of live poultry markets or periodic thorough disinfections of these markets in China and any other regions with live poultry markets.

Although this swelling of the ranks of avian flu viruses has yet to produce a pandemic virus, it is problematic on a number of fronts. First is the impact they are having on poultry production and trade around the globe. And while the number of human infections remains relatively low, they can be quite devastating to those affected.

But this recent expansion of flu viruses also makes the emergence of additional novel subtypes even more likely, as the more diverse and dense the playing field, the more `interchangeable’ genetic parts that are available for reassortment and the greater chance of co-infecting a common host..

The bottom line is, after a decade of pretty much only having one avian virus to worry about, over the past two years we’ve seen the emergence and spread of multiple clades of HPAI avian H5N8, H5N6, H5N3, and H5N2 along side H7N9, H10N8 and a handful of `minor players’ like canine & equine H3N8, canine H3N2, and even H10N7 in marine mammals.

And of course, we have no idea what new reassortants may appear over the next few years.

While no one can predict where any of these viruses will end up - the greater the diversity of novel viruses in circulation - the greater the chances of someday seeing one successfully adapt to humans.

.

For more on this rapidly expanding array of novel flu viruses you may wish to revisit:

The Expanding Array Of Novel Flu Strains

EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment

Viral Reassortants: Rocking The Cradle Of Influenza