#18,740

Last December an ostrich farm in British Columbia reported unusual mortality among their birds, and in early January HPAI H5N1 was confirmed by the CFIA.

That agency order culling - the long-standing recommendation of WOAH/OIE (see below) - of the remainder of the exposed birds.

Control strategies and compensation for farmers

When an infection is detected in poultry, a policy of culling infected animals and the ones in close contact is normally used in an effort to rapidly contain, control and eradicate the disease.

Selective elimination of infected poultry, movement restrictions, improved hygiene and biosecurity, and appropriate surveillance should result in a significant decrease of viral contamination of the environment. These measures should be taken whether or not vaccination is part of the overall strategy.

The farm owners have fought a protracted legal battle to prevent this culling, which has become a cause célèbre online, and in the political arena.

Yesterday the CFIA published an update which adds a new wrinkle to this 5-month saga; the announcement that (at least some of) these ostriches were infected with a novel genotype (D1.3), which was identified in a sick Ohio poultry worker last February.

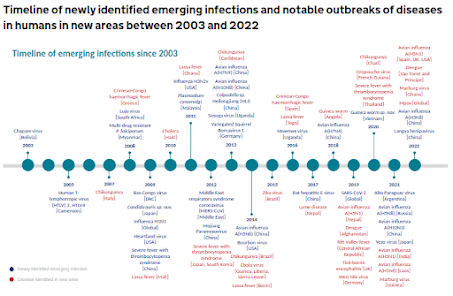

Although more than 100 genotypes of H5N1 have been reported in North America since the H5 virus arrived in late 2021, over the past 15 months we've seen 4 new genotypes of note emerge in the United States and Canada.

- B3.13 aka the `bovine' strain affecting dairy cattle in at least 16 states and mildly infecting dozens of humans

- D1.1 a wild bird/poultry strain which has spilled over into > a dozen people in Washington State, severely infected a teenager in British Columbia, and produced a fatal infection in Louisiana.

- D1.2 a wild bird/poultry strain which recently detected in poultry and 2 pigs in Oregon

- D1.3 a recently detected wild bird/poultry strain which has been infection poultry and at least 1 human

While we are only hearing about it 5 months after-the-fact, this first reported outbreak of genotype D1.3 in Western Canada pre-dates the Ohio outbreak by a couple of months.

While much of this announcement centers on the government's case for culling these birds, what arguably should have been the lede (in red) is buried about 1/3rd the way down the page.

Update on the Canadian Food Inspection Agency's actions at an HPAI infected premise at a British Columbia ostrich farm

From: Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Statement

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and Canada's national poultry sectors have been responding to detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in Canada since December 2021. Industry has been highly supportive of the CFIA in its response to HPAI, working collaboratively to implement control measures and protect animal health.

The CFIA has acted to minimize the risk of the virus spreading within Canadian flocks and to other animals. All avian influenza viruses, particularly H5 and H7 viruses, have the potential to infect mammals, including humans. Our disease response aims to protect public and animal health, minimize impacts on the domestic poultry industry, and the Canadian economy.

The CFIA's response to highly pathogenic avian influenza in domestic poultry is based on an approach known as “stamping-out”, as defined by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) Terrestrial Animal Health Code. Stamping-out is the internationally recognized standard and is a primary tool to manage the spread of HPAI and mitigate risks to animal and human health as well as enable international trade. It includes steps to eliminate the virus from an infected premises, including the humane depopulation and disposal of infected animals, and disinfection of premises.

There are ongoing risks to animal and human health and Canada’s export market access

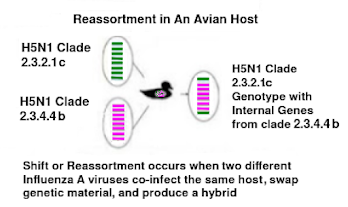

Allowing a domestic poultry flock known to be exposed to HPAI to remain alive means a potential source of the virus persists. It increases the risk of reassortment or mutation of the virus, particularly with birds raised in open pasture where there is ongoing exposure to wildlife.

CFIA’s National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease (NCFAD) identified that the current HPAI infection in these ostriches is a novel reassortment not seen elsewhere in Canada. This assortment includes the D1.3 genotype, which has been associated with a human infection in a poultry worker in Ohio.

A human case of H5N1 in BC earlier this year required critical care, and an extended hospital stay for the patient, and there have been a number of human cases in the United States, including a fatality.

Stamping-out and primary control zones enable international trade as it allows Canada to contain outbreaks within a specific area, meet the requirements of zoning arrangements with trading partners, and permit Canada’s poultry industry to export from disease-free regions. Continued export market access supports Canadian families and poultry farmers whose livelihoods depend on maintaining international market access for $1.75 billion in exports.

Current status of the infected premise at Universal Ostrich Farm

Universal Ostrich Farm has not cooperated with the requirements set out under the Health of Animals Act including failure to report the initial cases of illness and deaths to the CFIA and failure to adhere to quarantine orders. Universal Ostrich Farm was issued two notices of violations with penalty, totaling $20,000.

The farm also failed to undertake appropriate biosecurity risk mitigation measures such as limiting wild bird access to the ostriches, controlling water flow from the quarantine zone to other parts of the farm, or improving fencing. These actions significantly increase the risk of disease transmission and reflect a disregard for regulatory compliance and animal health standards.

Universal Ostrich Farm has not substantiated their claims of scientific research. CFIA has not received any evidence of scientific research being done at the infected premises.

Research documentation was not provided during the review of their request for exemption from the disposal order based on unique genetics or during the judicial review process. Further, the current physical facilities at their location are not suitable for controlled research activities or trials.

On May 13, 2025, the Federal court dismissed both of Universal Ostrich Farm’s applications for judicial review. The interlocutory injunction pausing the implementation of the disposal order was also vacated.

Following the May 13 court ruling, the farm owners and supporters have been at the farm in an apparent attempt to prevent the CFIA from carrying out its operations at the infected premises. This has delayed a timely and appropriate response to the HPAI infected premises, resulting in ongoing health risks to animals and humans.

CFIA’s next steps at the infected premises

Given that the flock has had multiple laboratory-confirmed cases of H5N1 and the ongoing serious risks for animal and human health, and trade, the CFIA continues planning for humane depopulation with veterinary oversight at the infected premises.

The CFIA takes the responsibility to protect the health of animals and Canadians extremely seriously as we conduct these necessary disease control measures to protect public health and minimize the economic impact on Canada's poultry industry.

For more detailed information on the CFIA’s continued response to HPAI at this infected premises, please visit our website.

Understanding the origins and spread of novel genotypes, subtypes, and certain mutations in HPAI viruses are all critical if we hope to get some kind of control over this growing epizootic.

Last April Canada was singled out for being one of the slowest nations in releasing non-human HPAI sequence information (see Nature: Lengthy Delays in H5N1 Genome Submissions to GISAID).

Today's belated announcement only appears to further cement that reputation.