# 8842

Between the frequent hyperbolic demonization of influenza antivirals (see Daily Mail: Ministers blew £650MILLION on useless anti-flu drugs) by media critics of `Big Pharma’, spurred on by repeated Cochrane group analyses that have found insufficient evidence that the drug reduces influenza complications, it probably comes as little surprise that many doctors – particularly in outpatient settings – tend to underutilize antiviral drugs, even for patients at the greatest risk for complications.

While well-respected, the Cochrane Group uses a very narrow (and some would say misguided) criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of antiviral drugs. One that discards all but a handful of studies.

Last April, in Revisiting Tamiflu Efficacy (Again), I wrote at some length on the BMJ – Cochrane Library review Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children – that examined a subset of the scientific literature and cast doubt on its effectiveness in treating influenza.

While I too lamented the lack of solid, well mounted Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) proving the effectiveness of Oseltamivir (particularly in high risk patients, or with novel flu strains), I listed a number observational studies that strongly support the effectiveness of Oseltamivir.

A few days later, the CDC issued their own response. I’ve posted the link and some excerpts below. Follow the link to read their rationale in its entirety.

CDC Recommendations for Influenza Antiviral Medications Remain Unchanged

April 10, 2014 -- CDC continues to recommend the use of the neuraminidase inhibitor antiviral drugs (oral oseltamivir and inhaled zanamivir) as an important adjunct to influenza vaccination in the treatment of influenza. CDC’s current influenza antiviral recommendations are available on the CDC website and are based on all available data, including the most recent Cochrane report, about the benefits of antiviral drugs in treating influenza.

(Continue . . .)

The CDC considers those a higher risk of influenza complications, and for whom they recommend antiviral treatment for suspected or confirmed influenza , to include:

- children aged younger than 2 years;

- adults aged 65 years and older;

- persons with chronic pulmonary (including asthma), cardiovascular (except hypertension alone), renal, hepatic, hematological (including sickle cell disease), metabolic disorders (including diabetes mellitus) or neurologic and neurodevelopment conditions (including disorders of the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerve, and muscle such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy [seizure disorders], stroke, intellectual disability [mental retardation], moderate to severe developmental delay, muscular dystrophy, or spinal cord injury);

- persons with immunosuppression, including that caused by medications or by HIV infection;

- women who are pregnant or postpartum (within 2 weeks after delivery);

- persons aged younger than 19 years who are receiving long-term aspirin therapy;

- American Indians/Alaska Natives;

- persons who are morbidly obese (i.e., BMI is 40 or greater); and

- residents of nursing homes and other chronic-care facilities.

But based on a new study, published this week in Clinical Infectious Diseases, antiviral drugs for these cohorts appear to be underutilized. Worse, patients were twice as likely to be prescribed antibiotics than antivirals for influenza.

Fiona Havers1, Swathi Thaker2, Jessie R. Clippard2, Michael Jackson3, Huong Q. McLean4, Manjusha Gaglani5, Arnold S. Monto6, Richard K. Zimmerman7, Lisa Jackson3, Josh G. Petrie6, Mary Patricia Nowalk7, Krissy K. Moehling7, Brendan Flannery2, Mark G. Thompson2, and Alicia M. Fry2

Abstract

Background. Early antiviral treatment (≤2 days since illness onset) of influenza reduces the probability of influenza-associated complications. Early empiric antiviral treatment is recommended for those with suspected influenza at higher risk for influenza complications regardless of their illness severity. We describe antiviral receipt among outpatients with acute respiratory illness (ARI) and antibiotic receipt among patients with influenza.

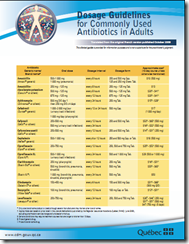

Methods. We analyzed data from 5 sites in the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network Study during the 2012–2013 influenza season. Subjects were outpatients aged ≥6 months with ARI defined by cough of ≤7 days’ duration; all were tested for influenza by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Medical history and prescription information were collected by medical and pharmacy records. Four sites collected prescribing data on 3 common antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate, amoxicillin, and azithromycin).

Results. Of 6766 enrolled ARI patients, 509 (7.5%) received an antiviral prescription. Overall, 2366 (35%) had PCR-confirmed influenza; 355 (15%) of those received an antiviral prescription. Among 1021 ARI patients at high risk for influenza complications (eg, aged <2 years or ≥65 years or with ≥1 chronic medical condition) presenting to care ≤2 days from symptom onset, 195 (19%) were prescribed an antiviral medication. Among participants with PCR-confirmed influenza and antibiotic data, 540 of 1825 (30%) were prescribed 1 of 3 antibiotics; 297 of 1825 (16%) were prescribed antiviral medications.

Conclusions. Antiviral treatment was prescribed infrequently among outpatients with influenza for whom therapy would be most beneficial; in contrast, antibiotic prescribing was more frequent. Continued efforts to educate clinicians on appropriate antibiotic and antiviral use are essential to improve healthcare quality.

In an accompanying press release from the Infectious Diseases Society of America we get the following summary:

Findings suggest antivirals underprescribed for patients at risk for flu complications

Study also shows that antibiotics may have been prescribed unnecessarily

(EXCERPT)

Overall, only 19 percent of the patients at high risk for influenza-associated complications who saw a primary-care provider within two days of the onset of their symptoms received antiviral treatment. Among patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza, just 16 percent were prescribed antivirals. In contrast, 30 percent of these patients received one of the three antibiotics.

"Our results suggest that during 2012-'13, antiviral medications were underprescribed and antibiotics may have been inappropriately prescribed to a large proportion of outpatients with influenza," the authors wrote. "Continuing education on appropriate antibiotic and antiviral use is essential to improve health care quality."

While some of the antibiotics may have been appropriate for bacterial infections secondary to influenza, which is caused by a virus, it is likely most were unnecessary, potentially contributing to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance, the authors noted.