Credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

# 10,075

In January of 2014, an emerging HPAI H5N8 appeared in South Korean poultry and wild birds, and although it appears to have originated in China the previous year, it suddenly took off. It showed up next in Japan, and subsequently showed up across much of China, in Russia, Western Europe, Taiwan, and North America.

Apparently at home in migratory birds, this well-traveled H5N8 virus has reassorted with several local LPAI viruses, producing viable, and highly pathogenic hybrids (H5N2, H5N3, H5N1, etc.) – which taken together have cost the world’s poultry industry billions of dollars over the past 15 months (see Taiwan hit by new type of H5N2, H5N8 for first time).

As with all of the avian flu viruses we’ve been watching, these influenza subtypes (i.e. H5N8 or H5N1) don’t represent a single entity, but rather a family of closely related viruses, all able to `better themselves’ through the evolutionary process.

As a result, new variants and clades are constantly appearing either through antigenic drift or reassortment. Some fail miserably and quickly fade away, while others are competitive and `biologically fit’ enough to prosper.

We’ve heard a lot about the genetic diversity of H5N1 and the need to update candidate vaccines over the years (see WER: Development Of Candidate Vaccine Viruses For Pandemic Preparedness), but far less is known about how the H5N8 virus is evolving in the wild.

A little a year ago, in EID Journal: Describing 3 Distinct H5N8 Reassortants In Korea, we saw some early evidence of this evolutionary pattern, and last December in NARO: Miyazaki H5N8 Outbreak A Different Sub Clade we learned that a second variation on an H5N8 theme had turned up in a Japanese poultry outbreak.

Last fall (see Japan: H5N8 Detected In Izumi Crane) H5N8 was detected among wild and migratory birds in the Izumi bird preserve on southern tip of Japan, a place famed for the yearly arrival and overwintering of thousands of rare Hooded, and White-naped cranes.

Both species spend their summers in Mongolia, Siberia, or Northwestern China - and of the roughly 10,000 hooded swans in the world - 80% overwinter in Izumi.

All of which serves as prelude to a Rapid Communications that appears in today’s Eurosurveillance that describes the discovery of at least 3 genetically distinct groups of the H5N8 virus.

Eurosurveillance, Volume 20, Issue 20, 21 May 2015

Rapid communications

M Ozawa (

)1,2,3,4, A Matsuu2,3,4, K Tokorozaki5, M Horie2,3, T Masatani2,3, H Nakagawa1, K Okuya1, T Kawabata2, S Toda5

We isolated eight highly pathogenic H5N8 avian influenza viruses (H5N8 HPAIVs) in the 2014/15 winter season at an overwintering site of migratory birds in Japan. Genetic analyses revealed that these isolates were divided into three groups, indicating the co-circulation of three genetic groups of H5N8 HPAIV among these migratory birds. These results also imply the possibility of global redistribution of the H5N8 HPAIVs via the migration of these birds next winter.

In January 2014, newly discovered highly pathogenic H5N8 avian influenza viruses (H5N8 HPAIVs) caused outbreaks in poultry and wild birds in South Korea [1], although their ancestor had been isolated in China in 2013 [2]. Thereafter, these viruses have been circulating in both avian populations in South Korea [3,4] and sporadically in neighbouring countries, including China and Japan. Since November 2014, H5N8 HPAIVs have also appeared in poultry and wild birds in Europe [5,6]. Genetic analyses revealed that these isolates were closely related to the H5N8 viruses circulating in Korean birds. More recently, genetically similar HPAIVs also caused outbreaks in various avian species in North America [7]. These findings suggest that the H5N8 viruses have circulated and evolved in migratory birds.<SNIP>

Phylogenetic analysis

To understand the genetic relationship between our isolates and related viruses, the HA and neuraminidase (NA) genes were phylogenetically analysed with counterparts from the representative avian influenza H5 (Figure 2A) and N8 (Figure 2B) subtypes, respectively.We found that the H5 genes from our eight isolates belonged to clade 2.3.4.4 and were genetically divided into three groups. The water isolate, A/environment/Kagoshima/KU-ngr-H/2014(H5N8), fell into a phylogenetic cluster together with the European isolates and was closely related to two wild duck isolates in Japan (Group A, indicated in green in the Figures). The first and second crane isolates, A/crane/Kagoshima/KU1/2014(H5N8) and A/crane/Kagoshima/KU13/2014(H5N8), were genetically similar to the North American isolates (Group B, blue in the Figures). The HA genes of the rest of our isolates (Group C, red in the Figures), as well as a poultry isolate from Japan were clearly distinct from those of the other recent H5N8 isolates. These findings suggest that three genetically distinct groups of H5N8 HPAIVs were independently circulating among the migratory birds at the Izumi plain.

Intriguingly, the genetic grouping of our isolates matched broadly the dates of sampling; the forth to eighth isolates were categorised into Group C, while earlier isolates were categorised into Group A or B. To determine whether this virus group has genetic characteristics that become predominant among the migratory birds over the remaining virus groups, further investigation would be needed.

<SNIP>

No mutations were found that are known to confer the ability to infect mammalian hosts or to provide resistance against anti-influenza drugs to avian influenza viruses, with the exception of an asparagine at position 31 in the M2 protein, which confers resistance to the M2 ion channel blocker amantadine [11].

Conclusion

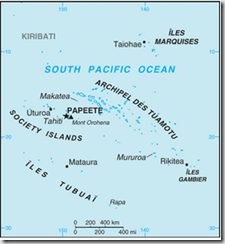

We isolated eight H5N8 HPAIVs from migratory birds and the water in their environment at the Izumi plain in southern Japan. Based on their genome sequences, these isolates were genetically divided into three groups. These results indicate the co-circulation of at least three genetic groups of H5N8 HPAIVs among the migratory birds overwintering at a single site in Japan. These H5N8 HPAIVs are most likely to be derived from wild ducks [12], rather than from cranes whose flyways were restricted to East Asian countries (Figure 1A). These findings also imply the possibility of global redistribution of the H5N8 HPAIVs via migration of these ducks next winter.

The birds that overwintered in Japan, Korea, and the Pacific Northwest last fall are now gathered in their summer breeding sites in northern China, Mongolia and Siberia - sharing lakes, ponds, and streams and no doubt, the occasional avian virus - and will be winging their way south again in a few short months.

What new viral variants, clades, or reassortments we will see next fall and winter when they return is anyone’s guess.