# 7376

Along with last night’s early release MMWR (see MMWR: MERS-CoV Update – June 7th) the CDC released an updated HAN Health Update on the MERS coronavirus.

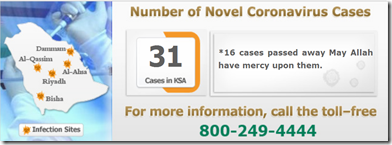

Although no cases have been reported in the United States - with the source of the virus still unknown, and millions of religious pilgrims expected to travel to Saudi Arabia over the next four months – the chances of that remaining the case are far from sure.

Hence the flurry of activity this week at the CDC on MERS-CoV and the the H7N9 virus (see CDC: Updated H7N9 Guidance Docs).

This HAN update is geared primarily towards Health Care Providers and public health officials, so I’ll not reproduce the entire document. Those interested in the specifics will want to follow the link to read the update in its entirety.

This is an official

CDC HEALTH UPDATE

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

June 7, 2013, 20:00 ET 08:00 PM ET

CDCHAN-00348Notice to Health Care Providers: Updated Guidelines for Evaluation of Severe Respiratory Illness Associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

Summary

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working closely with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other partners to better understand the public health risk posed by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a novel coronavirus that was first reported to cause human infection in September 2012. No cases have been reported in the United States. The purpose of this HAN Advisory is to provide updated guidance to state health departments and health care providers in the evaluation of patients for MERS-CoV infection including expansion of availability of laboratory testing and, in consultation with WHO, expansion of the travel history criteria for patients under investigation from within 10 to 14 days for investigation and modification of the case definition. Please disseminate this information to infectious diseases specialists, intensive care physicians, internists, infection preventionists, as well as to emergency departments and microbiology laboratories.

<SNIP>

Surveillance

As a result of investigations suggesting incubation periods for MERS CoV may be longer than 10 days, the time period for considering MERS in persons who develop severe acute lower respiratory illness days after traveling from the Arabian Peninsula or neighboring countries* has been extended from within 10 days to within 14 days of travel.

In particular, persons who meet the following criteria for “patient under investigation” (PUI) should be reported to state and local health departments and evaluated for MERS-CoV infection:

- A person with an acute respiratory infection, which may include fever (≥ 38°C , 100.4°F) and cough; AND

- Suspicion of pulmonary parenchymal disease (e.g., pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome based on clinical or radiological evidence of consolidation); AND

- History of travel from the Arabian Peninsula or neighboring countries* within 14 days; AND

- Symptoms not already explained by any other infection or etiology, including clinically indicated tests for community-acquired pneumonia† according to local management guidelines.

In addition, the following persons may be considered for evaluation for MERS-CoV infection:

- Persons who develop severe acute lower respiratory illness of known etiology within 14 days after traveling from the Arabian Peninsula or neighboring countries* but who do not respond to appropriate therapy; OR

- Persons who develop severe acute lower respiratory illness who are close contacts‡ of a symptomatic traveler who developed fever and acute respiratory illness within 14 days of traveling from the Arabian Peninsula or neighboring countries.*

In addition, CDC recommends that clusters of severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) should be investigated and, if no obvious etiology is identified, local public health officials should be notified and testing for MERS-CoV conducted if indicated.

CDC requests that state and local health departments report PUIs for MERS-CoV and clusters of SARI with no identified etiology to CDC. To collect data on PUIs, please use CDC’s Interim Health Departments MERS-CoV Investigation Form available at http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidance.html.

State health departments should FAX completed investigation forms to CDC at 770-488-7107 or attach in an email to eocreport@cdc.gov (subject line: MERS-CoV Patient Form).

(Continue . . . )