Credit CDC PHIL

# 9258

Yesterday author, blogger, and scary disease girl extraordinaire Maryn McKenna featured a long-read by risk communications experts Dr. Peter Sandman & Dr. Jody Lanard (see her wired blog The Grim Future if Ebola Goes Global) on the conversation that no one in authority seems willing to have right now:

What happens if Ebola is not contained in West Africa?

First, a strong recommendation to read the analysis by Sandman & Lanard in its entirety if you haven’t already, after which I’ll have a bit more.

Ebola: Failures of Imagination

by Jody Lanard and Peter M. Sandman

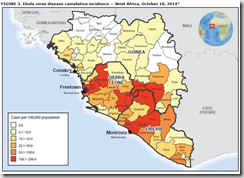

The alleged U.S. over-reaction to the first three domestic Ebola cases in the United States – what Maryn McKenna calls Ebolanoia – is matched only by the world’s true under-reaction to the risks posed by Ebola in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. We are not referring to the current humanitarian catastrophe there, although the world has long been under-reacting to that.

We will speculate about reasons for this under-reaction in a minute. At first we thought it was mostly a risk communication problem we call “fear of fear,” but now we think it is much more complicated.

(Continue . . . )

Highly recommended.

Admittedly, I too have found it hard to paint a bleak picture of where this Ebola epidemic could lead – partially, I think as a subconscious pushback against the over-the-top fear mongering that is all too rampant online, and partially due to my deep-seated ex-paramedic mindset of `No matter how bad things get, don’t get rattled, just carry on.’

And to be very clear, while my crystal ball is cracked and fogged up badly, my `bleak picture’ isn’t one of massive Ebola epidemics sweeping across the nation, or mass graves in the developed world.

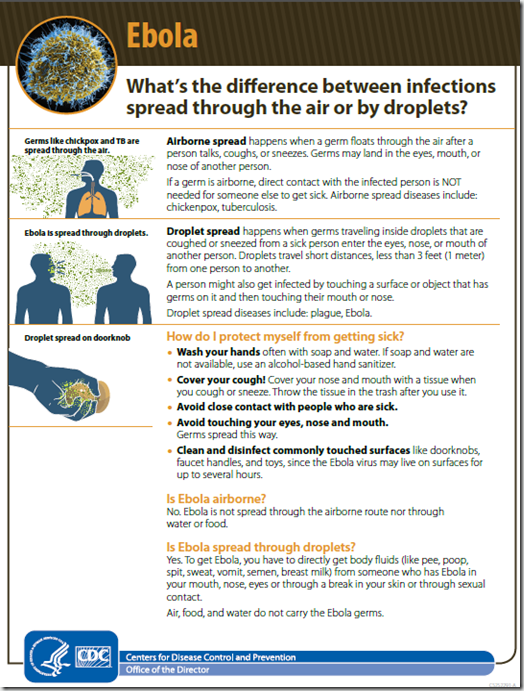

While there are respiratory pathogens out there capable of such carnage, I don’t believe Ebola (in its present incarnation, anyway) to be one of them.

NOTE: The `weasel wording’ in the previous sentence is 100% intentional, as I think it is important to push back against the absolute assurances constantly being uttered by nervous officials.

Previously, in An Appropriate Level Of Concern Over Ebola In The US, I wrote:

That is not to say we won’t see impacts from this epidemic. We already have – in Dallas – and I quite expect we will again. We could certainly see limited spread here, and even small clusters of cases. And while it won’t be pretty, and the response may not be perfect, I have enough faith in our public health infrastructure to believe they would be able to control it.

Now, if Ebola ever finds a way to spread through the mega-cities of Africa, India, Pakistan, or some other high-population, low resource region of the world – the economic, societal, and political destabilization that could occur might change both the nature, and degree, of this epidemic’s threat to the developed world.

A veiled vision, cloaked in ambiguity, that only tentatively hints at what failure to contain the virus in Africa could mean to the rest of the world. Hindered, no doubt, by my own personal `failure of imagination’, and by the difficulties of accurately projecting the impact of a slow-motion strain wreck.

An epidemic that spreads inexorably – not over weeks or months – but potentially over years.

Spreading more like HIV, TB, or Hepatitis than what we might expect from an emerging pandemic virus. Unlike those scourges, however, Ebola kills very quickly – in a matter of days – which increases its immediate impact.

How that might play out on the global stage six months or a year from now is very tough to envision, but in a world already roiled in crises, its impact can’t be ignored.

Over the years we’ve looked at the real possibility of seeing a Black Swan Event – a world-changing incident that few, if anyone, had predicted. The phrase was coined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his 2004 book Fooled By Randomness, and expanded upon in his 2007 book The Black Swan.

Black swan events can arise in a lot of different ways, and various national security documents over the years have analyzed, and warned about, many possible scenarios.

- A Pandemic

- A Cyber Attack

- A Financial Crisis

- A Geomagnetic Storm

- Social Unrest/Revolution

It is no coincidence that a severe pandemic ranks at the top of almost every list of highly disruptive national security threats (see 2011 OECD Report: Future Global Shocks, UK: Civil Threat Risk Assessment, Influenza Pandemic As A National Security Threat).

Is Ebola a black swan event? I honestly don’t know. But it could be if it isn’t contained.

And right now, despite the upbeat messaging that `we know how to stop Ebola’, there are too many unknowns to be overly confident in the outcome. Some may say that `failure is not an option’, but the truth is, history is replete with failures.

We just tend to call them something else in the history books.

When my wife and I moved aboard our cruising sailboat in 1986, we immediately purchased a combination inflatable dingy/life raft. We didn’t plan on sinking, but we also knew the ocean might have other plans for us. So with the kind of fatalism only longtime liveaboard sailors can muster, we christened it `Plan B’.

I’m happy to report it was never used for anything more desperate than rowing ashore to pick up another case of beer. But it was there, equipped and ready, for any emergency.

While I hope we don’t ever need it, we need to be thinking about what our collective Plan B will be, if Ebola isn’t contained in West Africa. And that means thinking about, publicly talking about, and planning for the kind of disruptions that might occur if the virus makes its way to the mega-cities of Africa, India, China, or South America.

Eight years ago the governments of the world urged agencies, organizations, businesses, and individuals to take a good hard look at their daily operations, and plan on how they would cope during a severe influenza pandemic. Since the relatively mild pandemic of 2009, the idea of pandemic planning has largely fallen to neglect.

Now might be a very good time to dust off your old pandemic plans, update them as necessary, and encourage others to do so.

Because, if Ebola doesn’t turn out to be the next great global public health crisis, there are plenty of other contenders waiting in the wings that could.