Zhejiang Province – Credit Wikipedia

Editor's note: I'm 14 hours post cataract surgery and supposedly taking a break, but Sharon Sanders on FluTrackers has picked up an interesting report from China on a fatal dual infection with Avian H10N5 and seasonal H3N2 influenza in a woman from Anhui province (hospitalized in Zhejiang province).

#17,887

First the (translated) statement as it appears on China's NHC website, after which I'll have more on the timeline, along with a brief review of H10 human infections and the ever-present concerns from dual influenza A infections.

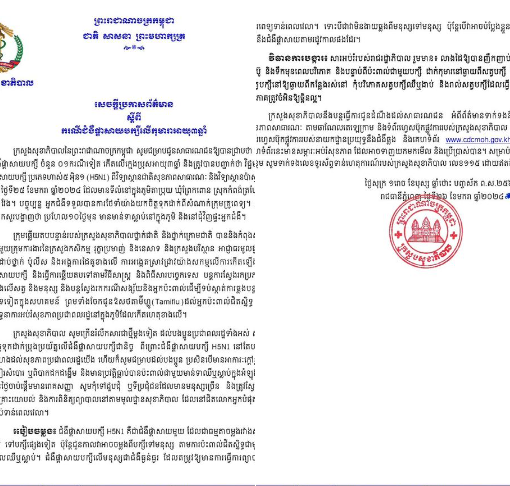

A case of H3N2 and H10N5 mixed infection discovered in Zhejiang Province

Date: 2024-01-30 Source: Emergency Response Department

The National Administration for Disease Control and Prevention reported that a case of H3N2 and H10N5 mixed infection was discovered in Zhejiang Province.

The patient is a 63-year-old female from Xuancheng, Anhui Province. She has multiple underlying diseases in the past. Symptoms such as cough, sore throat, and fever developed on November 30, 2023; on December 2, he was admitted to a local medical institution for treatment due to his worsening condition; on December 7, he was transferred to a medical institution in Zhejiang Province for hospitalization. Died on the 16th.

During a retrospective study of fatal cases, Zhejiang Province isolated seasonal H3N2 subtype and avian H10N5 subtype influenza viruses from case specimens on January 22, 2024. On January 26, the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a re-examination and testing of specimens submitted for inspection in Zhejiang, and the results were consistent with previous results. Zhejiang and Anhui provinces have conducted medical observation on all close contacts, and no abnormalities were found, and nucleic acid screening was negative; through retrospective case searches, no suspicious cases were found during the same period.

The National Administration of Disease Control and Prevention has guided Zhejiang and Anhui provinces to carry out prevention and control in accordance with relevant plans and organized experts to conduct risk assessments. Experts assessed that the complete genetic analysis of the virus showed that the H10N5 virus was of poultry origin and did not have the ability to effectively infect humans. The epidemic was an occasional cross-species transmission from poultry to humans. The risk of the virus infecting humans is low and no human-to-human transmission has occurred.

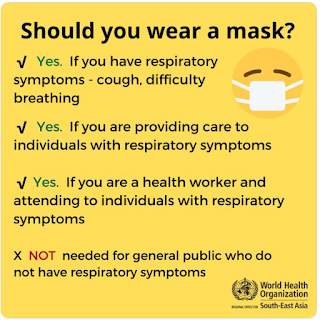

Experts suggest that the public should avoid contact with sick and dead poultry in daily life and try to avoid direct contact with live poultry; pay attention to dietary hygiene and improve self-protection awareness. If you have fever and respiratory symptoms, you should wear a mask and seek medical treatment as soon as possible.

This cases was apparently only discovered 7 weeks after her initial hospitalization, and 5 weeks after her death, due to a policy of retrospectively testing samples from fatal flu cases in China. This delay makes the `negative results' from close contacts somewhat less probative than they may appear.

We've seen studies suggesting that surveillance is lucky if it picks up 1 in 200 novel flu cases (see CID Journal: Estimates Of Human Infection From H3N2v (Jul 2011-Apr 2012), and seroprevalence studies of poultry workers showing very high titers to various subtypes of avian flu.The reality is, it takes more than a bit of luck for a novel flu case to be picked up by surveillance in China, or anywhere else. Most people with flu-like symptoms never seek medical help, and of those that do, only a small percentage (usually only in sentinel hospitals) end up tested for subtype.

Ten months ago, in UK Novel Flu Surveillance: Quantifying TTD, we looked at a UKHSA assessment stating that it could take hundreds of community cases, over several weeks, before HPAI H5N1 might be picked up by routine passive surveillance.

In countries or regions with less sophisticated testing, surveillance and reporting capabilities, limited community transmission might take much longer to detect. Absence of evidence isn't the same as evidence of absence.

Although it tends to get less attention than H5, H7, or even H9 subtypes, avian H10 viruses have also shown a proclivity for spilling over into mammals (see Avian H10N7 Linked To Dead European Seals), and occasionally, infecting humans.

HK CHP: A Cryptic Report of A 2nd H10N3 Case On the Mainland

Cell Host & Microbe: Avian H10N7 Adaptation In Harbor Seals

Jiangxi Province Reports 3rd H10N8 Case

While this mixed H3N2/H10N5 infection appears to have been a dead-end - with no recognized onward transmission of H10N5 or a H10/N3 reassortment detected - humans (like birds, pigs, and other hosts) have the potential to act as mixing vessels for influenza viruses.

Twice in my lifetime (1957 and 1968) avian flu viruses have reassorted with seasonal flu and launched a human pandemic.

- The first (1957) was H2N2, which According to the CDC `. . . was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes.'

- In 1968 an avian H3N2 virus emerged (a reassortment of 2 genes from a low path avian influenza H3 virus, and 6 genes from H2N2) which supplanted H2N2 - killed more than a million people during its first year - and continues to spark yearly epidemics more than 50 years later.

While a seasonal flu/avian flu hybrid might not be as deadly as full-on avian virus, it might spread a lot easier in humans (see The `Other Mixing Vessel' For Pandemic Influenza).

While this is likely a rare, or `one-off' event, it reminds us that nature throws the genetic dice countless times every day around the world, and it only has to get `lucky' once to plunge us into another public health crisis.

For the next day or so (or until my post-op vision improves) you'll want to check back with Flutrackers for the latest updates.