Figure 1 - Source BMC Medicine

# 8673

The internet has provided new and more efficient ways to accrue, organize, and access epidemiological data and has spawned multiple projects to identify, quantify, and dissect disease outbreaks.

Over the year’s we’ve looked at a number of these projects, including the efforts of volunteer flu forums (including FluTrackers & The Flu Wiki), crowd-sourced data-gathering platforms like Flu Near You, Healthmap, ProMed Mail, and Google’s Flu Trends, and of course the analysis and work product of scientist-bloggers like Dr. Ian Mackay, Andrew Rambaut, and Maia Majumder.

Last April, ECDC director Marc Sprenger noted the contribution of these, and other `crowd epidemic intelligence’ efforts online, in a Eurosurveillance editorial called - Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus – two years into the epidemic M Sprenger, D Coulombier – by writing:

Interestingly, over the past two years, voices on social media have been increasingly important for reports about the MERS-CoV situation as they have kept the topic high on the agenda of by raising pertinent questions, curating content on blogs, and reporting on cases in near-real time via Twitter. We have seen the MERS CoV debate on Twitter engage bloggers and journalists along with public health organisations, epidemiologists and doctors alike, often resulting in faster reporting and better understanding of the situation. This debate relates to a new phenomenon called ‘crowd epidemic intelligence’ [12] and is particularly important given the many unknowns about the MERS epidemic.

Regular readers of this blog are no doubt familiar with how often I refer to FluTracker’s MERS and H7N9 case lists, and so I was gratified to see among the references cited in this article was:

- Flutrackers, 2012-2014 Case List of MoH/WHO Novel Coronavirus nCoV Announced Cases. Available from: http://www.flutrackers.com/forum/showthread.php?t=205075.

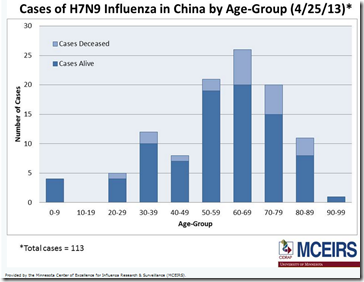

Of course, FluTrackers maintains just one of several such lists, which brings us to a new study – published today in BMC Medicine – that compares the `official’ Chinese CDC line list of H7N9 cases to 5 publicly-sourced listings:

- Health Map

- Virginia Tech

- Bloomberg News

- The University of Hong Kong

- FluTrackers

This is an open-access study, so follow the link to read it in its entirety:

Eric HY Lau, Jiandong Zheng, Tim K Tsang, Qiaohong Liao, Bryan Lewis, John S Brownstein, Sharon Sanders, Jessica Y Wong, Sumiko R Mekaru, Caitlin Rivers, Peng Wu, Hui Jiang, Yu Li, Jianxing Yu, Qian Zhang, Zhaorui Chang, Fengfeng Liu, Zhibin Peng, Gabriel M Leung, Luzhao Feng, Benjamin J Cowling and Hongjie Yu

BMC Medicine 2014, 12:88 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-12-88

Published: 28 May 2014Abstract

Background

Appropriate public health responses to infectious disease threats should be based on best available evidence, which requires timely reliable data for appropriate analysis. During the early stages of epidemics, analysis of ‘line lists’ with detailed information on laboratory confirmed cases can provide important insights into the epidemiology of a specific disease.

The objective of the present study was to investigate the extent to which reliable epidemiologic inferences could be made from publicly-available epidemiologic data of human infection with influenza A(H7N9) virus.

Methods

We collated and compared six different line lists of laboratory-confirmed human cases of influenza A(H7N9) virus infection in the 2013 outbreak in China, including the official line list constructed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention plus five other line lists by Health Map, Virginia Tech, Bloomberg News, the University of Hong Kong and FluTrackers, based on publicly-available information.We characterized clinical severity and transmissibility of the outbreak, using line lists available at specific dates to estimate epidemiologic parameters, to replicate real-time inferences on the hospitalization fatality risk, and the impact of live poultry market closure.

Results

Demographic information was mostly complete (less than 10% missing for all variables) in different line lists, but there were more missing data on dates of hospitalization, discharge and health status (more than 10% missing for each variable). The estimated onset to hospitalization distributions were similar (median ranged from 4.6 to 5.6 days) for all line lists. Hospital fatality risk was consistently around 20% in the early phase of the epidemic for all line lists and approached the final estimate of 35% afterwards for the official line list only.Most of the line lists estimated >90% reduction in incidence rates after live poultry market closures in Shanghai, Nanjing and Hangzhou.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that analysis of publicly-available data on H7N9 permitted reliable assessment of transmissibility and geographical dispersion, while assessment of clinical severity was less straightforward. Our results highlight the potential value in constructing a minimum dataset with standardized format and definition, and regular updates of patient status. Such an approach could be particularly useful for diseases that spread across multiple countries.