Photo Credit (Wikipedia)

# 6457

This week, with news of another small cluster of H3N2v infections in Indiana (see MMWR On The H3N2v Outbreak In LaPorte, Indiana), our attention has turned once again to the potential for a novel swine-origin influenza virus to spread among humans.

For now, the CDC sees no no signs of sustained and efficient transmission of the H3N3v virus in humans, and the public health threat appears low.

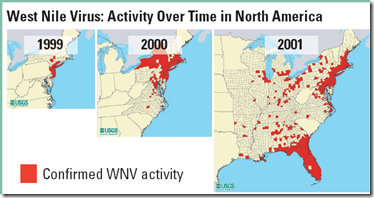

And with luck, this virus will end up being nothing more than an interesting footnote in influenza history. But experience shows that swine flus can jump species, and in rare instances, can even cause a pandemic.

While the world was watching for a bird flu pandemic in 2009, we were blindsided by a descendent of a triple reassorted H1N1 swine flu virus that first appeared in North American pigs in the late 1990s.

It spread through swine herds – picking up genetic changes as it went - for at least a decade before it evolved to spread efficiently among humans.

Granted, the adaptation of a novel swine flu virus to humans is a rare event, and for every successful virus, there are undoubtedly an untold number of failures.

We occasionally see limited transmission of SOIV (Swine-Origin Influenza Viruses) to humans, mostly among people in direct contact with infected livestock.

For the most part, these viruses don’t appear to transmit well between people - and so far - only rarely are these infections passed on to others.

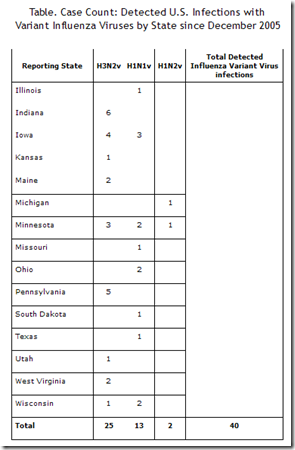

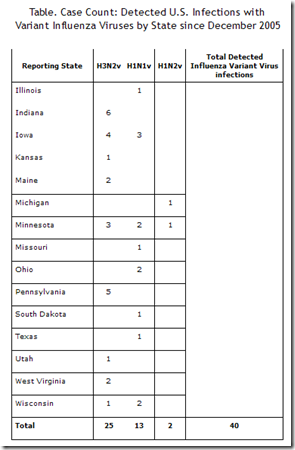

Since 2005 the CDC has documented 40 SOIV human cases (excluding the 2009 H1N1 virus) in the U.S., representing three main strains (H3N2v, H1N1v, H1N2v). Since the summer of 2011, it has been the H3N2v (variant) swine virus which has dominated.

These 40 cases certainly don’t represent the full burden of human infection by these variant viruses, but so far none of these swine flu viruses appear ready for primetime.

It is axiomatic however, that influenza viruses are constantly changing; evolving via two well established routes; Antigenic drift and Antigenic Shift (reassortment).

Antigenic drift causes small, incremental changes in the virus over time. Drift is the standard evolutionary process of influenza viruses, and often come about due to replication errors that are common with single-strand RNA viruses.

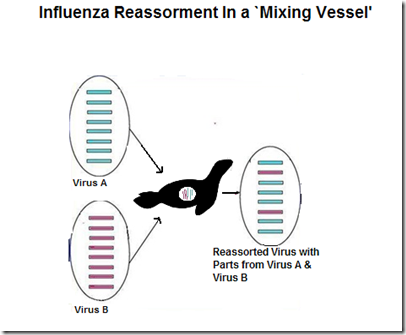

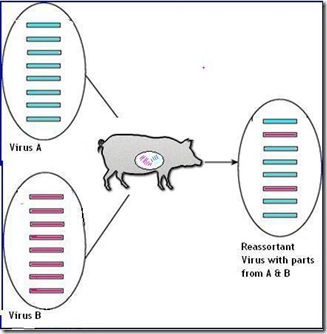

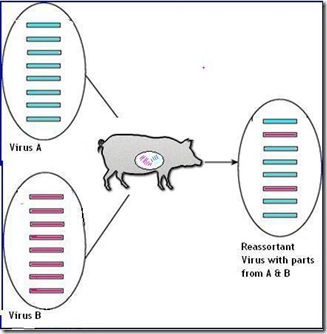

Shift occurs when one virus swap out chunks of their genetic code with gene segments from another virus. This is known as reassortment. While far less common than drift, shift can produce abrupt, dramatic, and sometimes pandemic inducing changes to the virus.

For shift to happen, a host (human, swine, bird) must be infected by two influenza different viruses at the same time. While that is relatively rare, as any virologist will tell you . . . Shift happens.

Reassortment of two Flu viruses

Despite constantly changing, the vast majority of these viruses will prove to be evolutionary dead ends; providing no advantage in replication or transmissibility.

So H3N2v may never turn into a serious public health threat. Only time will tell.

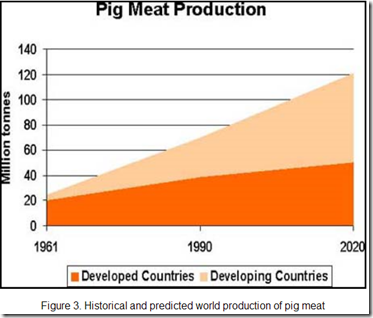

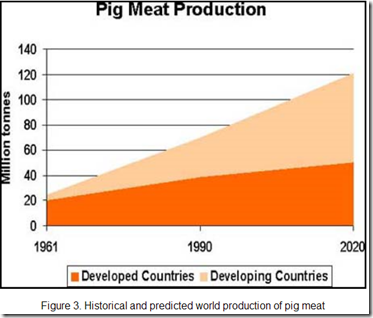

But as pig production expands to feed a growing global population - we add millions more `mixing vessels’ to nature’s laboratory every year – giving novel flu viruses more opportunities to evolve or mutate.

As the chart below shows, the bulk of this growth in hog farming over the next decade is expected in developing countries, where there is little biosecurity, testing or surveillance.

Source: FAO

Diseases that might never have taken hold on the family farm with a dozen hogs or chickens have a far better chance to spread and mutate once introduced into our modern CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations) where thousands of pigs or hundreds of thousands of birds are crowded into close quarters.

Complicating matters – in the interest of economy – livestock are not always raised, fattened, and processed close to home. It is often cheaper to ship a pig to the Midwest – where the feed is – than to ship the feed to where the pig was bred.

And after fattening, hogs may be shipped to yet another state for processing.

The math is simple: a well-traveled pig has more opportunities to pick up, or spread a novel virus than one that never leaves the farm of its birth.

For more perspective on all of this, I heartily recommend Dr. Michael Greger’s free online book Bird Flu: A Virus Of Our Own Hatching, and Helen Branswell’s terrific piece in SciAm from late 2010 called Flu Factories.

The next pandemic virus may be circulating on U.S. pig farms, but health officials are struggling to see past the front gate

By Helen Branswell | December 27, 2010 |

Vegan dreams aside, the world in not likely to give up the commercials raising of pigs, chickens, and other livestock for meat.

Which makes the prevention, detection, and containment of zoonotic diseases a priority.

Since county fairs are a nexus where pigs and humans come together, earlier this week the CDC offered Offered Advice To Fair Goers on avoiding infection.

The CDC has also produced guidance to people who raise pigs and for commercial hog farms to help minimize the risks from Swine flu. These stress the importance of workers getting the seasonal flu shot every year (to protect the pigs, as much as the humans), good hand hygiene, and where appropriate, the use of PPEs (Personal Protective Equipment).

Unfortunately, between economic losses suffered during the 2009 `swine flu’ pandemic, and a general feeling that the public health threat from influenza in pigs is overstated, many hog farmers have shown reluctance to allow testing of their herds (see Swine Flu: Don’t Test, Don’t Tell).

And even assuming that American pig producers stringently follow the CDC guidelines (which can only lower the risks), there remain millions of farm operations around the world where no such biosecurity measures are in place.

While the next pandemic could come from a wild bird in Asia, or the bushmeat trade out of Africa (see Bushmeat,`Wild Flavor’ & EIDs), the odds favor it coming from a commercial farm somewhere in the world where large numbers of animals intermingle, swap viruses, and come in daily contact with humans.

Which is why increasing our surveillance of livestock (and humans) for zoonotic diseases must become a global priority.

It may not be possible to prevent next pandemic virus from emerging - but the earlier we spot it - the better shot we will have at limiting its spread and the more time we will have to produce and deploy a vaccine.

For more on swine flus, and viral reassortment, you may wish to revisit some of these earlier blogs: