#17,142

Although it can be confusing, there are many different clades (varieties) of avian H5N1 viruses in the wild, some of which are more pathogenic to humans than others. The clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 virus which is currently affecting poultry and wild birds - and the occasional human - in Europe and North America is not the same as its deadlier Asian cousins.

While they share a common ancestor, the European H5N1 virus has (thus far) only produced mild or asymptomatic infections in humans, while some Asian H5 clades have a double-digit fatality rate.

With that in mind we have a (belated) report out of Mainland China of a fatal infection with H5N1 in a 38-year-old woman from Guangxi Province. She fell ill and was hospitalized in September, and died in October. While the clade isn't given, based on its severity, this is almost certainly one of the Asian strains.

China, which is dealing with a variety of internal problems (see China At The Pandemic Crossroads) is often slow to report avian flu cases - or any other `bad news' for that matter - which is why `no news' doesn't always mean `good news' when it comes to Mainland China.

Today's report from Hong Kong's CHP follows. I'll have a bit more after the break.

CHP closely monitors human case of avian influenza A(H5N1) in Mainland

The Centre for Health Protection (CHP) of the Department of Health is today (November 30) closely monitoring a human case of avian influenza A(H5N1) in the Mainland, and again urged the public to maintain strict personal, food and environmental hygiene both locally and during travel.

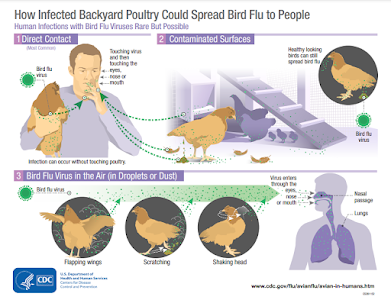

The case involves a 38-year-old woman living in Qinzhou, Guangxi, who had exposure to live domestic poultry before onset. She developed symptoms on September 22 and was admitted for treatment on September 25. She passed away on October 18.

From 2005 to date, 54 human cases of avian influenza A(H5N1) have been reported by Mainland health authorities.

"All novel influenza A infections, including H5N1, are notifiable infectious diseases in Hong Kong," a spokesman for the CHP said.

Travellers to the Mainland or other affected areas must avoid visiting wet markets, live poultry markets or farms. They should be alert to the presence of backyard poultry when visiting relatives and friends. They should also avoid purchasing live or freshly slaughtered poultry, and avoid touching poultry/birds or their droppings. They should strictly observe personal and hand hygiene when visiting any place with live poultry.

Travellers returning from affected areas should consult a doctor promptly if symptoms develop, and inform the doctor of their travel history for prompt diagnosis and treatment of potential diseases. It is essential to tell the doctor if they have seen any live poultry during travel, which may imply possible exposure to contaminated environments. This will enable the doctor to assess the possibility of avian influenza and arrange necessary investigations and appropriate treatment in a timely manner.

While local surveillance, prevention and control measures are in place, the CHP will remain vigilant and work closely with the World Health Organization and relevant health authorities to monitor the latest developments.

The public should maintain strict personal, hand, food and environmental hygiene and take heed of the advice below when handling poultry:The public may visit the CHP's pages for more information: the avian influenza page, the weekly Avian Influenza Report, global statistics and affected areas of avian influenza, the Facebook Page and the YouTube Channel.

- Avoid touching poultry, birds, animals or their droppings;

- When buying live chickens, do not touch them and their droppings. Do not blow at their bottoms. Wash eggs with detergent if soiled with faecal matter and cook and consume the eggs immediately. Always wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling chickens and eggs;

- Eggs should be cooked well until the white and yolk become firm. Do not eat raw eggs or dip cooked food into any sauce with raw eggs. Poultry should be cooked thoroughly. If there is pinkish juice running from the cooked poultry or the middle part of its bone is still red, the poultry should be cooked again until fully done;

- Wash hands frequently, especially before touching the mouth, nose or eyes, before handling food or eating, and after going to the toilet, touching public installations or equipment such as escalator handrails, elevator control panels or door knobs, or when hands are dirtied by respiratory secretions after coughing or sneezing; and

- Wear a mask if fever or respiratory symptoms develop, when going to a hospital or clinic, or while taking care of patients with fever or respiratory symptoms.

Ends/Wednesday, November 30, 2022

Issued at HKT 17:00

Although it is undoubtedly a major undercount, prior to 2021 the World Health Organization had confirmed 862 human infections with the `Asian' H5N1 virus (see chart below). Of those, 455 (52%) died.

This doesn't include the 80+ cases of H5N6 reported by China, the 1500+ cases of H7N9, or any of the other occasional spillovers of avian flu (H9N2, H3N8, H10N8, etc.) that often go unreported.

Last month we saw the release of ECDC Guidance For Testing & Identification Of Zoonotic Influenza Infections In Humans In The EU/EAA, while CDC Guidance can be found HERE.While infections with H5N1 and H5N6 are sporadic, and H7N9 is now (at least temporarily) controlled by China's massive poultry vaccination campaign, the concern is that these viruses can intermingle, and even share genetic material, meaning that a `mild' H5N1 virus today may not remain so forever.

To date, all known human influenza pandemics have involved only H1, H2, and H3 viruses, and there is some debate over whether an H5 virus can actually join that exclusive club.

But the same skepticism existed about novel coronaviruses not so many years ago, and we now know how well that turned out.